A visit to the Crossness pumping station

In the early nineteenth century, the River Thames was heavily polluted. It was treated as an open sewer, with human excrement and industrial waste dumped directly into the river and left to rot. The uncleaned river led to multiple outbreaks of cholera, and made central London thoroughly unpleasant. In summer 1858, the hot weather made the smell so bad that it was dubbed “the Great Stink”. At this time, many people believed that bad smells (called miasma) were responsible for the spread of disease, so the state of the river was seen as a public health hazard.

After 1858, Parliament decided to commission a new, modern sewerage system that would carry the smell away from the centre of the city. The Metropolitan Board of Works – led by engineer Joseph Bazalgette – were tasked with building the new sewers. I first came across the story in a BBC docudrama series, which has quite a nice overview.

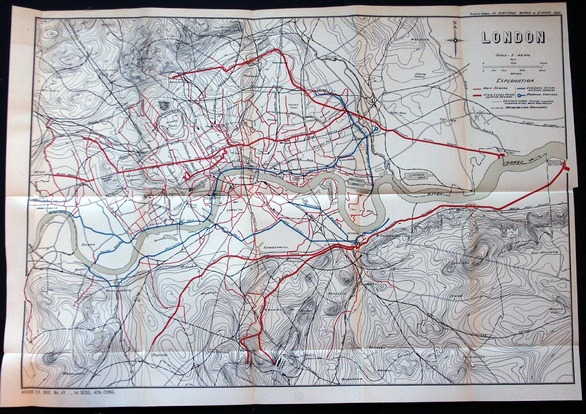

The design of this new system was rather elegant: a series of six main tunnels (three either side of the river) would carry the sewage east, away from the city. Smaller sewers would carry sewage from individual properties into the main tunnels. The whole system was built on a gradient, so everything is carried entirely by gravity. When it’s sufficiently far east, the sewage is pumped back up to ground level, dumped in the Thames and washed out to sea.

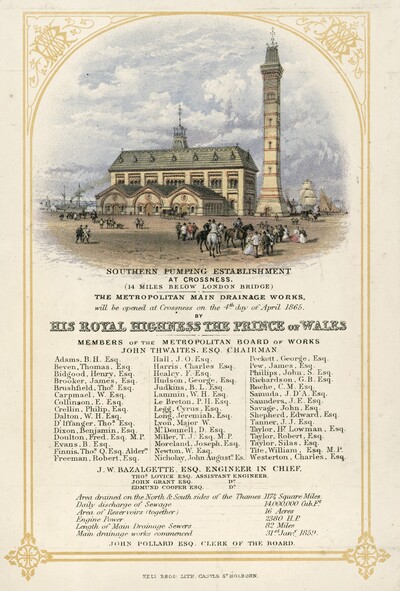

The endpoint of the southern tunnel was at Crossness. There was a pumping station with four steam-driven pumps that pulled the waste up to ground level, and dumped it into the river on the outgoing tide. Both Crossness and the wider sewerage system were seen as major feats of Victorian engineering, and the opening of Crossness itself was a particularly prestiguous event.

Today we’re (slightly) more enlightened, and don’t just dump raw sewage into the sea. Instead, sewage is sent to treatment plants for processing, and disposed of elsewhere – which led to these old pumping stations being decommissioned. By the end of 1950s, these stations were all but abandoned.

Since then, the other southern pumping station (Deptford) has essentially vanished, and the northern station (Abbey Mills) is a shell of its former self. But Crossness survived fairly well: the large chimney in the invitation above was demolished, but otherwise the site was left in reasonable shape. In 1985, the Crossness Engines Trust was established to preserve the site, and restore the engines to a working state. Today, the pumping station is open to the public.

Last weekend, Crossness were running an open day - the pumping station was open to the public, and they were running the restored engine. Given my interest, I decided to head down, have a look round, and take a few photos.

It turns out that Crossness is a bit of a trek from a Cambridge – over three hours! I got a train and two tubes to Woolwich Arsenal, then walked the remaining three miles to Crossness. Although tiring, this wasn’t entirely without merit – the route takes you along the top of the Ridgeway, a path that runs along the top of the southern outfall sewer. This was a first glimpse of the sheer scale of this project – you get some idea of the size of the tunnel beneath you.

As I approached Crossness itself, my first sight wasn’t something I’d typically associate with “Victorian pumping station”. Today, there’s a sewage treatment plant at Crossness, with the Engines themselves in the original buildings, somewhat off to the side. I still had a little more walking to do!

Up the hill, and I finally got my first glimpse of the engine house. Although viewed from a different angle, you can see the resemblance to the building in the opening invitation.

Carrying on round the side, I found the entrance to the building, and you can see the three rooves from the invitation. Out of shot to the right was the village green around which the workers’ houses were built. Because Crossness was relatively far out, a lot of the workers lived on-site, and in a somewhat forward-thinking move, housing was built at the same time as the main station. But I turned left, and went into the main exhibition.

In the main engine house, there’s an exhibition about the Great Stink. Lots of information about London’s sewer system, their construction, and what’s happening with London’s sewage today. It’s remarkable to see how well the Victorian system lasted – as with many engineering projects, it was built with plenty of room to grow. Although it’s had to expand to cope with London’s ever-increasing population, the original system was very robust.

Pumping London’s sewage to ground level required a huge amount of power. Crossness was driven by four massive steam engines – Victoria, Prince Consort, Albert Edward and Alexandra – built by the James Watt company (the same Watt as in the unit of power). These were rotative beam engines – likely the largest in the world. Collectively, they could burn over 5,000 tons of coal a year. But when Crossness was decommissioned, the engines were left to rust – too massive to be worth disassembling.

Today, volunteers for the Engine Trust have restored the Prince Consort to working condition. The other three engines are still in a partial or complete state of disrepair, but they still give you a sense of scale. Here’s a picture of the atrium, with one of the flywheels visible in the background – and you can just see a beam poking out behind the pillar.

Each flywheel is 27′ in diameter, and weighs 52 tons – and there were four of them. These wheels were so masisve that when they were built, they had to be cast in eight separate pieces, and joined together on site. You can just make out two of the joins in this photograph:

But then I went through to the main attraction – the working Prince Consort. Over nearly 28 years, volunteers at the Crossness Engine Trust worked to restore this engine to its original working condition (as of 1899 – more below). Here’s the big wheel, in all its resplendent glory:

Even more impressive, the engine was actually steaming. I deliberately picked a day when the engines were running:

The engine has a graceful, almost hypnotic motion. For a machine of such immense power, it moves in quite a slow and graceful way. Mesmerising – I could have sat and watched it for hours.

You can make out the connecting rod in the foreground, I got a second video of that moving:

(Unfortunately my phone was almost out of battery, so these are my only two videos.)

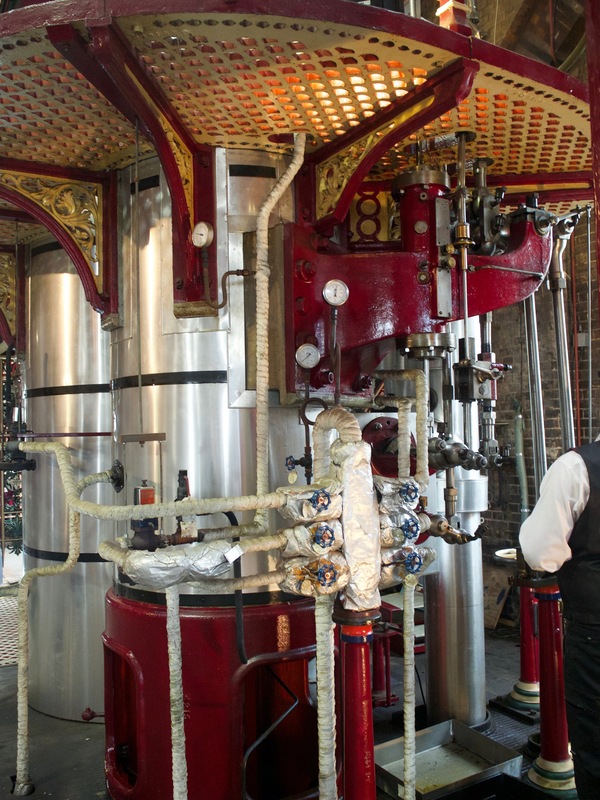

At the top of the beam, you can see the rocking beam – more of that in a moment. At the other end of the beam are the steam cylinders. The original engines only had a single cylinder, but in 1899, they were upgraded to a triple-expansion system to cope with London’s increasing sewage needs. That’s why Prince Consort was restored to its post-1899 state – this was the newer iteration of the engine. There are three cylinders: high, medium and low pressure, with exhaust steam from each flowing from each. Here’s a picture of the cylinders joining the main rocking beam:

The left-hand rocking beam was another late addition, added to upgrade the pumping capacity.

Here’s another picture of the back of the cylinders:

Then I went upstairs for a better view of the rocking beam. Each one is over 50′ long:

It’s so cool seeing the system move, with all the connecting pieces. Most modern technology is as small as possible – useful, but there’s something incredibly visceral about seeing all the moving parts. Watching such a mighty machine move is a humbling experience – after seeing this, all my software work feels a bit insignificant.

Even the rusting beams of the other three engines are an impressive sight:

The Victoria engine is under restoration, although it’s nowhere near complete – getting the engines back to working order is a lengthy and expensive affair.

As well as upstairs, you can head downstairs, and see some of the restoration work up close. Covered in dust, rust and scaffolding – but this is right in the belly of the beast. My camera struggled a bit with the low light, but I got a few pictures:

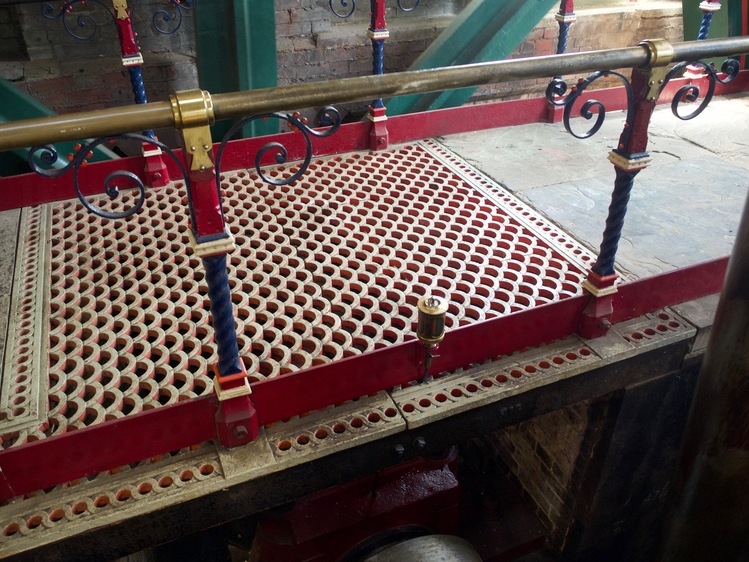

Finally, I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention the decorated ironwork – something for which Crossness was renowned. This wasn’t just an industrial site, it was a spectacle – every part of the interior had intricate delication and paintwork. At the centre of the site is the Octagon, where light entered the building:

The metalwork has been restored beautifully:

No part of the station – not even the floors, stairs or the handrails – escaped the ornate decoration.

The whole site was a fascinating day out. The engine has been restored beautifully, and there were some lovely volunteers who helped explain what I was actually seeing – even some in period dress! There’s something incredibly tangible and vivid about a steam engine the size of a building that you just don’t get from modern technology.

Crossness runs about four open days a month – details on their website – and I would really recommend going if you can. For the best experience, pick when the engines are actually running (or in their terms, “steaming”).