My visit to the Aberdulais Falls

In September, I was in Cardiff to help organise PyCon UK. I had a huge amount of fun at the conference, but running a five-day event gets quite tiring. This year I took a few days of extra holiday, so I could unwind before returning home. Unfortunately heavy storms kept me inside for several days, but I did venture out at the end of the week to the Aberdulais Falls.

Aberdulais is a village in south Wales, about 45 minutes drive from Cardiff, and a place with a long industrial history. It had easy supplies of coal and wood, and it sits atop a powerful river – the River Dulais. Today the former tin plate works are owned and managed by the National Trust, and I decided to go have a look.

Etymology note: the word Aberdulais is Welsh for mouth of the river Dulais. Aber is a Celtic prefix that appears in lots of place names. Well-known examples are places like Aberdeen and Aberystwyth.

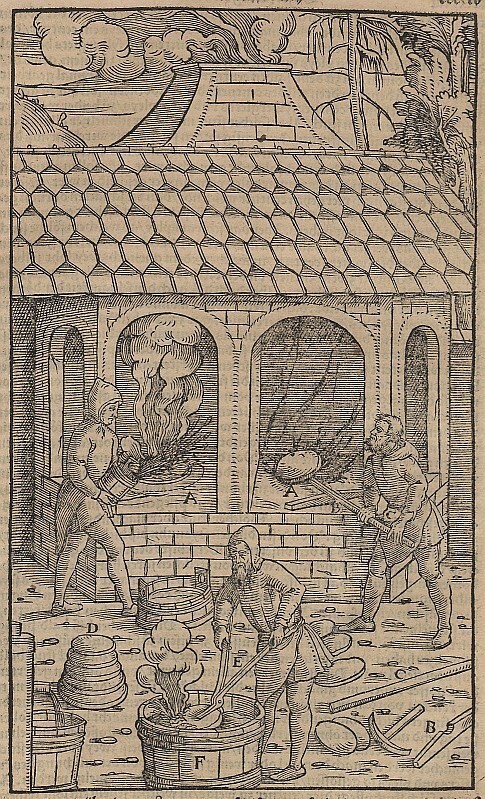

In 1584, German engineer Ulrich Frosse had developed a new way to smelt copper, but he wanted to keep his process safe from “pryinge eyes”. The Welsh countryside is nice and quiet, so he set up a smelting works in Aberdulais – the first of its kind in Wales. The copper ore was mined in Cornwall, the coal and charcoal supplied from nearby Neath, and a waterwheel on the river powered the site. (If you’re interested, I found an 1880 lecture that gives more detail about the history of smelting in Wales.)

The National Trust site says the copper was used in coins minted for Queen Elizabeth I. I tried to find some pictures of the coins in question, but I couldn’t find not enough detail to pick them out. Based on dates, I think it would have been something like this gold pound, but that’s only a guess.

Over time, Aberdulais became a site of different industries – textile milling, cloth production, even a flour mill – then in 1831, it became the site of a tinplate works. Tin plating is the process of coating thin sheets of iron or steel with tin, so they don’t rust. Tin plate is used for things like cooking utensils and canned food, and versions of it are still in use today. Wales had an incredibly successful tin plating industry – so much so that the US slapped massive tariffs on it, and shut the whole thing down.

The National Trust site is based in the remains of one of the old tin plating works.

So what’s it like to visit?

The car park is just across the road from the entrance, and I couldn’t see the falls as I was walking up. But as I approached, I could see a broken bridge, and hear and feel the power of the water crashing against it. I could hear it before I saw it.

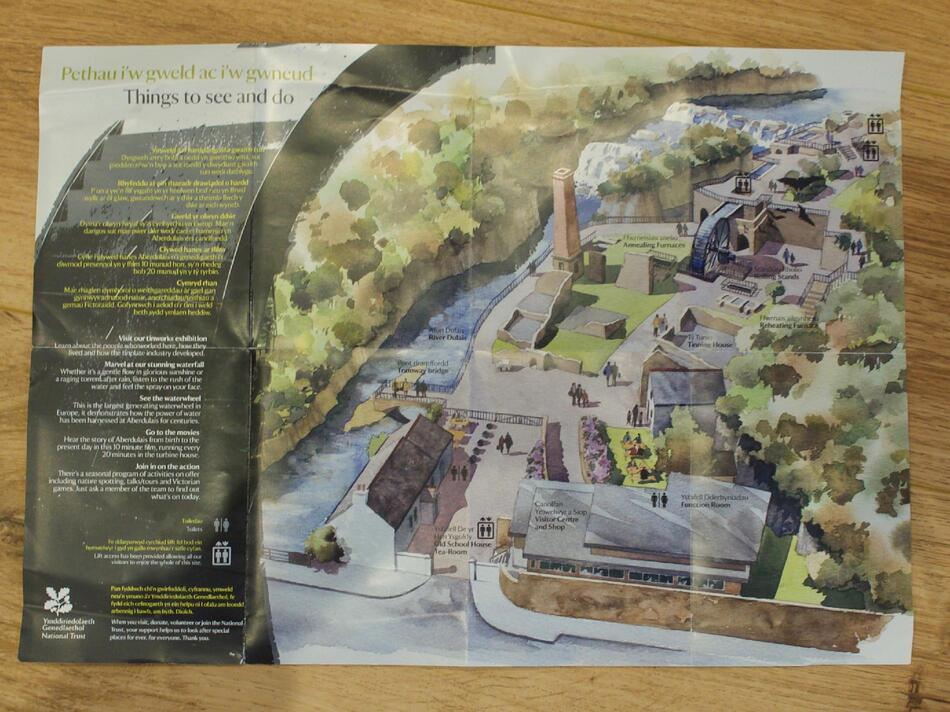

I went in, picked up a leaflet and a map from the visitor centre, and started wandering around. Here’s a photo of the leaflet, to give you an idea of the layout of the site. It’s on the smaller side, and you can easily do a visit in a couple of hours:

On the other side of the entrance, I could get a closer look at the bridge I’d seen from the road. You can see it’s partially broken off, but you can walk along it, and there’s a fence to stop people falling off the end.

This was originally a bridge meant for horses. It carried a tramway that led directly into the site, giving a way to cart materials in and out of the site. The horse-drawn carts would bring in the raw materials for the tinplate process, and later take out the finished product.

Like much of the site, the tramway and port are long since gone. The opposite side of the tramway is completely overgrown, and even if the bridge was rebuilt it wouldn’t go anywhere. Only a few remnants remain, such as the carts and the tracks they’d have run on:

Between pulling the carts, the horses needed a place to stop, rest, be fed and be re-shoed. Opposite the tramway were some stables and a blacksmith.

The stable buildings are still standing today, and they’re housing an exhibition about the tinplate process. It explains how tin plating works, the different jobs involved, and the stories of some of the people who actually lived and worked at Aberdulais. It includes a variety of pictures and illustrations showing what it was like to work in the tin plate industry.

It had just started to rain, so I was glad of an excuse to duck inside and start reading!

Once the weather had dried up, I ventured back outside, and I started wandering around the site. Although it was once a large industrial site, most of the buildings are long since gone – all you can see are remains. But as you wander round, you start to get an idea of the space the old tin works occupied.

Unfortunately there aren’t many details of what the buildings were used for – when the site was abandoned, the buildings were left to decay. Anything useful was taken away to the other tin plating works in Aberdulais, which didn’t close until many years later. There are information boards suggesting what some of the buildings were for, but they’re incomplete.

One thing that clearly stands out is the chimney, one of the few complete structures, which towers above the site.

This was the chimney for the annealing furnace. Annealing is the process of heating iron and steel to very high temperatures, allowing the internal structure to rearrange, and then cooling it back down. This makes the plates less brittle and more malleable, so the tinplates can be shaped without breaking.

At the base of the chimney, you can see the remains of some furnaces:

Another large structure was the “tin house”.

After the iron plates had been flattened and rolled into thin sheets, they’d be dipped in molten tin. After that, they’d be plunged into hot oil, which gave the plates a smooth and even finish. Once left to cool, you had the finished product – the prized tinplate. This process was done entirely by hand, was one of the more senior roles at the tin plate works, and it all happened in the tin house.

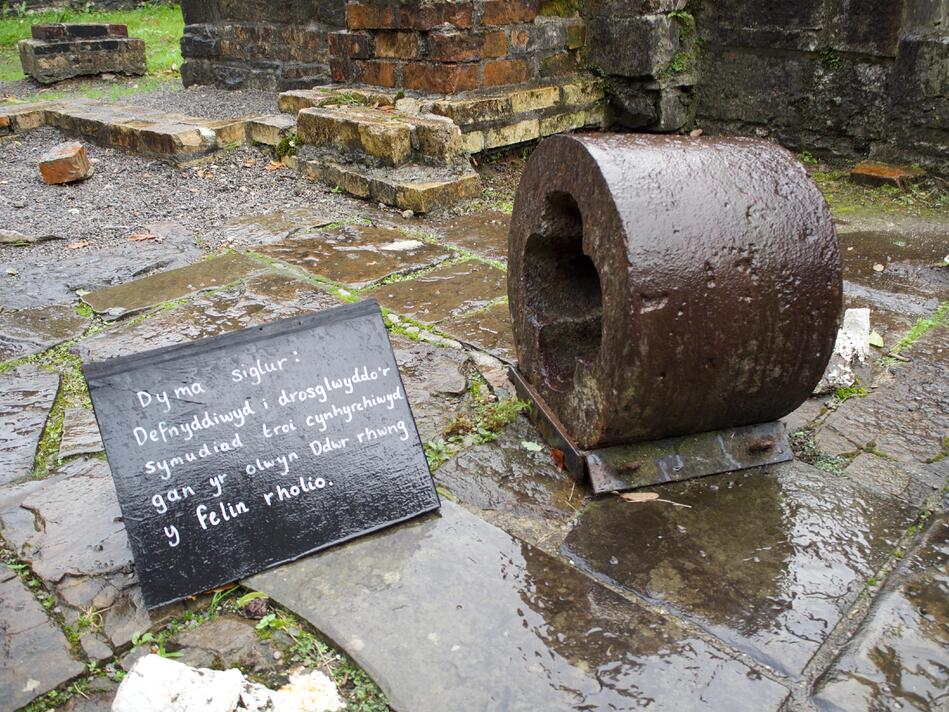

Stepping back from the buildings, dotted around the site are a variety of small objects related to tin plating or the site’s industrial history. Each of them has a small, handwritten sign explaining its significance: Here’s an example:

Other artefacts included a hook for retrieving slag from the iron furnace, and a metal plate that sat on the floor off the tin house. And since we’re in Wales, the signs were all written in Welsh as well as in English:

Near the tin house, there are parts of a drive shaft from one of the machines that used to work there, although I have no idea what machine it might have been a part of.

Looking past the buildings, if you follow the river, and climb to the top of the site, you get to the really impressive bit – the waterfall. This is the reason so much industry happened at Aberdulais. It’s a cheap, abundant source of energy, and even just standing near it you see the power of the water.

This was my first view of the falls: the upper half a browny-yellow sheet of water coming over the top, the lower covered in spray and mist. Even at a distance, the roar of the tumbling water really makes itself heard.

The sun came out as I wandered up, and I could see miniature rainbows in the spray coming off the water. So pretty!

Because I was standing so close, I could even change the shape of the rainbow by moving around. Here’s a second picture, taken when I was standing just a few feet to the right. Even a small movement affects the optics. The rainbow is just as intense, but it’s a noticeably different arc.

Both these rainbow pictures come straight from my camera, with just a bit of cropping. I didn’t do anything to boost the colour or brightness – the rainbows really are that visible!

Here’s another picture from the top of the falls, a sheer curtain of water coming over the top. I stood up there for a good fifteen, twenty minutes, watching the water flow, with spray hitting me in the face.

These are a few more of my favourite pictures of the falls. They’re a breathtaking, powerful sight, and the pictures really don’t do them justice:

Coming back down from the falls, I looked at the waterwheel that sits at the centre of the site. (I’d not gone near it on my first walk round.) Here’s a picture from above:

When I was there, I assumed it was historical. It wasn’t moving, so presumably it was a left over from when the days of industry?

Nothing could be further from the truth – it’s actually a working wheel! It was installed in 1991, and it’s the largest electricity-generating wheel in Europe. The wheel, along with some turbines that I didn’t see, power the entire site (including the visitor centre and tea rooms), and even sends surplus power back to the National Grid!

I wish I’d been able to see it spin, but maybe that’s a treat for another time.

Here’s another picture from on the ground, which gives you an idea of the size. It’s nearly 27′ in diameter, and it’s twice as tall as me even when half of it’s in the ground!

It’s nice to know that just because it’s become a heritage site, the power of the falls isn’t being wasted.

Here’s one last picture I took as I was on my way out – a last glimpse of the site. The water wheel, the remains of the buildings, and one more rainbow in the background.

If you want to see a bit of Welsh industrial history, and an incredibly scenic waterfall, I recommend a visit. Just don’t forget your raincoat!