Assume worst intent (designing against the abusive ex)

This is a talk I gave last Sunday at PyCon UK 2018.

Gail Ollis invited me to give a talk about online harassment in April, based on my talk about privilege and inclusion at the previous year’s conference. We were chatting afterwards, and I realised with a bit of tidying, I could reuse it. This is a refined and shortened (and hopefully better!) version of the April talk.

Here’s the abstract:

Apps and services often build features with good intent, trying to improve interactivity or connections between our users. But what if one of your users has a stalker, or an abusive ex? You may have given them another way to hurt or harass your user.

This session will help you identify common threat models – who is at most at-risk, and who is a threat to your most vulnerable users. Then we’ll look at some good practices that improve the safety of your users, and how to design with these risks in mind. There’s no silver bullet that totally eliminates risk, but you can make design decisions that give more control and safety to your users.

The talk was recorded, and you can watch it on YouTube:

You can read the slides and transcript on this page, or download the slides as a PDF. The transcript is based on the captions on the YouTube video, with some light tweaking and editorial notes where required.

Since you’ve already heard from me before, I’ll skip the introduction and gets right into the talk.

This morning we’re talking about online harassment, and specifically, how do we build systems to prevent it, reduce it, and reduce the risk of it. I’m going to show you some mechanisms and practical tips that I’ve found are most successful in reducing online harassment.

Before we start, some content warnings.

This is a talk about online harassment, so I’m going to talk about online harassment. I’m also going to talk about abuse.

There are mentions of things like racism, misogyny, sexism, suicide, rape and death threats. There are very brief mentions of some of the other horrible things that people do to each other on the Internet.

I’m aware that these are uncomfortable subjects for some people. People in this room may have traumatic experiences with these topics, and so while it’s usually considered poor etiquette to leave a talk midway through, if anybody does feel uncomfortable and wants to step out for a few minutes, I will absolutely not be offended.

[Ed. And if you’re reading the written version, you should only read on if you’re comfortable doing so!]

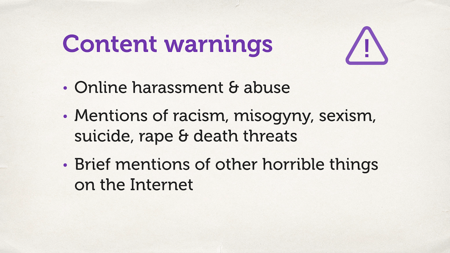

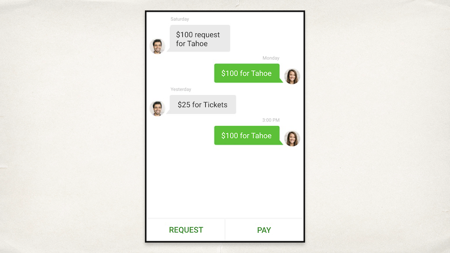

Let’s start off with an example. This is an app called Square Cash. It’s a nice little mobile payments platform. It’s designed to be fast, easy, more convenient than using online banking.

And as you can see in the screenshot, they have a chat feature. You can tell somebody why you would like money from them, and what they’re paying for. It gives you context for transactions – this seems like a really useful feature, right?

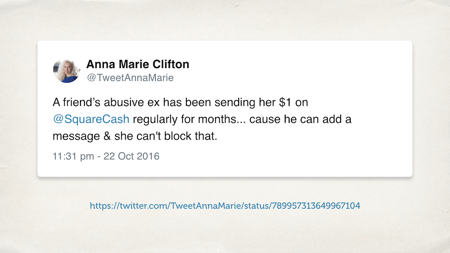

Except they didn’t realize that having a messaging platform opens the door to harassment. We can see here that somebody’s abusive ex used that messaging platform to send them abusive messages for months. Square Cash never thought to add a blocking feature, because why would you want to block somebody from sending you money? I like receiving money, you will like receiving money, money money money!

To their credit, when this tweet went viral, they very quickly closed a loophole – but it doesn’t change the fact that for months, somebody had to put up with harassment that was made possible through the design of their platform.

[Ed. Anna Marie’s original tweet is still up, and the topmost reply is from Robert Anderson – a founding designer at Square Cash.]

This is one of the big problems with thinking about user safety and harassment. If we let it be an afterthought, it becomes more expensive. It’s harder to retrofit later, and it often means that our users will learn the rough edges of our platform the hard way. User safety can’t be an afterthought.

This is a shame, because I fundamentally believe that most developers mean well. The Square Cash developers wanted to make a better way to send money to each other – they didn’t want to build a tool for harassment. I assume that most people at PyCon UK are pretty nice too.

How do we do this? How do we think about this?

Because a fundamental truth is this: if you allow user-to-user interactions, you have the possibility of harassment.

Ever since ever since we’ve had the means of communication – whether it’s talking, writing, sending images to each other – people have been using it to send nasty messages to other people. Most people are very nice, but there are some bad people out there and we do have to think about them.

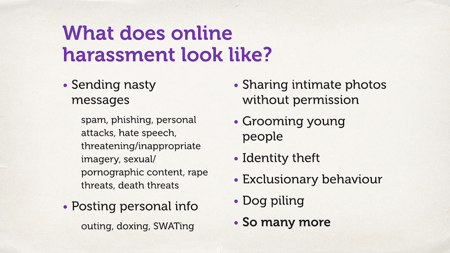

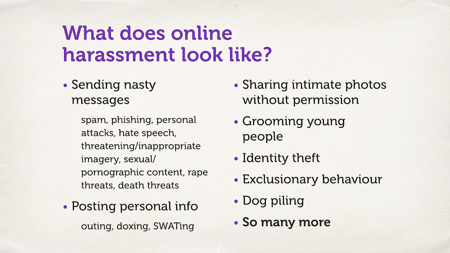

So what does online harassment look like?

These are some examples. There’s a lot of it.

- You’ll see things like sending nasty messages, and this goes all the way from spam and phishing, through to rape threats and death threats.

- Posting of personal information

- Identity theft

- Revenge porn

And many many more things that I’m sure you can think of that didn’t fit on this slide.

On the one hand, personal harassment isn’t a new thing. It didn’t suddenly spring up in the 1980s when we invented the Internet – people being harassed long before that. What online harassment changesis the scale and the scope.

The Internet allows me to talk to people halfway around the world – and that’s a fantastic thing, but it means that I can be harassed by somebody who I’ve never met in person, who I might never meet in person. They can still send me horrible messages.

And the rapid expansion of technology has enabled new vectors of for harassment. Take, for example, sharing intimate photos without permission, sometimes called revenge porn. Here, two people in a consensual, loving relationship take intimate photographs, and share them with each other. This is a fine thing to do between consenting adults, but thirty years ago you wouldn’t have been able to do that – making a photograph was relatively expensive. You needed a large camera, you’d go to a store to get the film developed, and sending photographs meant putting a stamp on an envelope.

Today we all have cameras in our pockets. I have at least three cameras standing at this podium, and we probably have at least 300 cameras in the room. It’s much much easier to take photographs, and it’s much, much easier to share them. That’s something that couldn’t have existed 30 years ago, and now is commonplace.

As technology continues to expand, new vectors of harassment crop up. We don’t have time to go into detail, but I’m assuming most of you are at least somewhat familiar with these things.

One thing I do want to stress is that this harassment has an impact on people. When I was younger, a lot of people used to say, “Online bullying and so on, it’s just words on the Internet. It doesn’t really matter. It doesn’t affect people.” Anybody heard that?

I’m seeing a few hands in the audience.

When I was younger, we all heard that, and I think a few of us believed it. And then one day we came into school and we were told that one of our friends wasn’t coming back. She’d been bullied on Facebook, and she’d jumped off a bridge. I was 16.

People stopped saying that words on the internet didn’t matter after that, but I think it was a bit late for her.

What people say on the Internet, what gets said through online platforms – that has an effect on people. It is a nasty thing. It’s not just words on the Internet. It’s not just words on a screen.

If you’re building a platform where people interact, where you have user-to-user interaction, I think you have a certain responsibility to consider what people there, and to think about the effects that might have beyond your platform.

This is all pretty nasty stuff – who’s doing it?

We have this popular image of a “hacker” – a malicious person on the Internet. This person ticks all the hacker stereotypes – they’re wearing a hoodie, they’re in a darkened basement, they have green text projected on their face.

This is the sort of person we need to worry about when we’re thinking about somebody stealing passwords from our database, or gaining root access to our servers, or doing malicious things against us as a service.

But I’m talking about with harassment is much more targeted – it’s directed against a particular person. The sort of people who do online harassment are the same as the people who do personal harassment in the physical world.

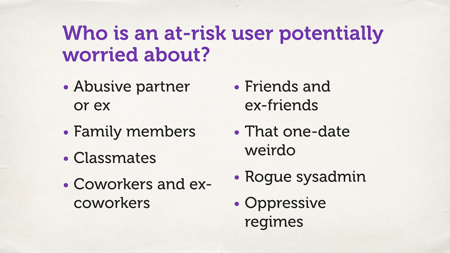

So let’s think about who those people might be.

It could be an abusive partner or an ex.

It could be family members.

It could be classmates. Kids often don’t have the best social skills, and will say pretty mean things.

Co-workers and ex co-workers.

Friends and ex friends.

That one-date weirdo. Another thing that the Internet has opened up for us – today there are many online dating sites, and in many ways this is a wonderful thing. But now before you ever meet somebody, they can download your entire Facebook profile, your Twitter feed, your Instagram photos. They know a huge amount about you – and if you decide that the data didn’t go so well, and they disagree, they now have many more wins of finding and tracking you later.

Rogue sysadmins. Do you know what your sysadmins are doing with your customer data?

Oppressive regimes. Something we’re lucky enough not to have to deal with in this country (mostly), but if you’re building a global service, you may have users in environments like that. And there are people who’d like to come after your users, who’d like to come after their data. You need to be thinking about that when you build your service too.

What you’ll notice about these is that none of these people are anonymous hackers who live in a basement in Russia and wear hoodies and drink bad coffee (Russia aren’t lucky enough to have Brodies).

The pattern we see with online harassment is the same as the pattern we see with personal harassment: people are more likely to be hurt by people they know.

This is very scary because a lot of the people we know are inherently more dangerous individuals, compared to anonymous faces on the Internet.

People like our family members or our friends. They have physical access to us. They probably know our intimate secrets They probably know the answer to your security questions.

Just out of curiosity, put your hands up in the room if you know somebody else’s phone passcode. [Ed. A bunch of hands went up.] Maybe that’s two-thirds of the room? And you’re all nice people, right? Right? (I’m not seeing the entire audience nodding, which is a little bit concerning.) Imagine if you were a nasty person. If you wanted to go through somebody else’s messages, go through their Facebook feed, go through their private texts – you could do that! You have access to do that.

Physical access makes these people quite scary, and nullifies a lot of the ways we might otherwise protect ourselves. All the security in the world doesn’t help if you have physical access to a person and their device.

And physical access can go beyond just our digital tools – it can also come down to simple acts of physical harm. Somebody who lives 600 miles away is going to struggle to physically hurt me, but somebody who lives in the same house as me will have very little trouble doing that.

This is all very upsetting.

There are horrible people in the world, they do horrible things, they might be living in the same house as you. Maybe we should all go and hide under a tin foil blanket and never leave our room.

This would not be particularly productive.

The good news is that it doesn’t have to be this way. There are tools and techniques we can use to build services in a way that reduces the risk of harassment.

We can never stop all the nasty people in the world, but we can do better. There are ways to build platforms that aren’t just open to all forms of abuse. We can do better than twitter.com.

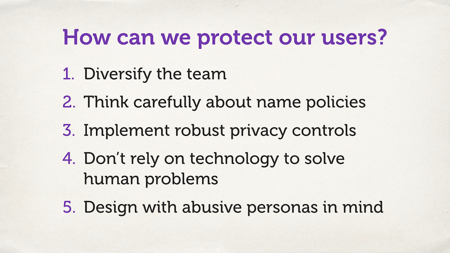

So how can we protect our users?

In the rest of this presentation, we’ll look at some ideas and best practices.

The first thing I want to stress is that a lot of users who get harassed are essentially normal users. They want to use your service for the same reasons as everyone else – that might be fun, work, creative projects – all sorts of reasons. The same reasons as anybody else.

Now, they might also be using it to look for an escape, to improve morale or find support – but a lot of the reasons will align with the rest of your users. This means that making your service better for users who are at high risk of harassment can make it better for everyone else.

As an example of this, conside email spam. Most of us probably get a small amount of emails, and a trickle of spam. If we were turned off our spam filtering, and let them all into our inbox, it would be annoying but not overwhelming. We could deal with it.

Spam filtering technology is essential for people who get overwhelmed in spam, drowning in thousands of messages a day. They couldn’t keep up with email if they didn’t have spam filtering. They absolutely need it.

But then we – people who don’t really need that – we get the benefits of that. In the same way, there are lots of ways these techniques can make a service better for everyone.

[Ed. David’s prolific live-tweeting informs me that this is called the “curb-cut effect”.]

What’s the first thing you can do?

First of all, diversify the team. I talked about this a lot last year, so I won’t go into much detail – the important thing to note is that we are all individuals. We all have a single lived experience, and there are people who are different from us, who have to worry about different things, who have to worry about different forms of harassment.

For example, I’m male. I don’t generally have to worry about being harassed at a tech conference. I don’t have to worry about being harassed on the bus. I don’t have to worry about what might happen if I’m sitting on the train and a slightly skeevy older dude sits down next to me.

I have some basic understanding of those things, but they don’t really permeate my sphere of consciousness in the same way they might if I was a woman. So if I’m designing a service, I want to have a woman on the team who has that lived experience, and who would instantly spot if I’m doing something that might be create a dangerous situation.

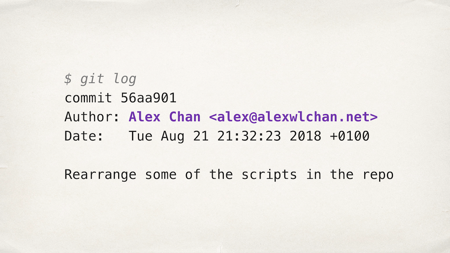

Let’s look at an example which I imagine many of you may have used. How many of you are familiar with Git?

Hands up in the room if you used Git. [Most of the hands are up.] Hands up if you’ve used Git today. [Most of the hands stay up.]

Git is a fantastic version control tool, and one of its features is that history is immutable. We do one-by-one commits, and then that history is immutable. Nobody can ever change it without fundamentally breaking history and it being very obvious. This is a good thing, that’s a feature, yes?

But one of the things that gets baked into the Git history, that you can never change, is your name. Your name is irrevocably part of the commit history. It’s available forever, and it’s publicly browsable in the history of a Git repository.

Can we ever think of scenarios where somebody would change their name? If you’ve not read the blog post “Falsehoods programmers believe about names”, I really recommend it, and this is a big one. There are lots of reasons somebody might change their name. They might get married and change their name (which predominantly happens to one gender), they might get divorced. They might want to hide the fact that they were once in a difficult marriage. They might be trans and want to get away from their deadname.

There are lots of reasons why somebody might want to change their name, and not have it baked into the history of a repository. Not have it permanently available.

When Git was originally put together in the early 2000s, I don’t think the Linux kernel team was particularly diverse. I don’t think they had many trans people on the team, because if they did, somebody might have looked at this and said, “Hey, is it a problem?”

There’s a lot of value in having a diverse team who can look at something like this, and tell you about it before you ship it to millions of users and only spot it 15 years… later when it’s a bit late.

[Ed. This slide is based on a blog post [How Git shows the patriarchal nature of the software industry](https://web.archive.org/web/20141230195605/http://blog.megan.geek.nz/how-git-shows-the-patriarchal-nature-of-the-software-industry/) which unfortunately now 404s.]

So think about diversifying the team.

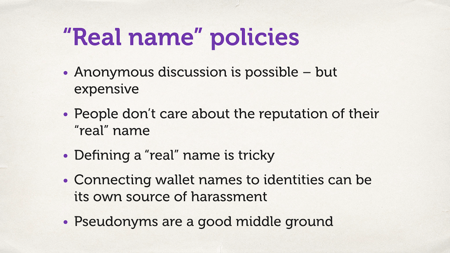

While we’re talking about names, let’s talk about name policies.

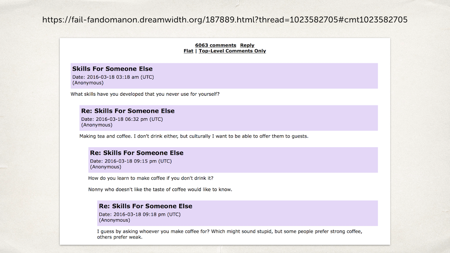

There’s a commonly held belief that if we ask everyone on the Internet to use their “real” name, that will magically make them behave. Anonymity causes all our problems, right? People can write anything without impunity, and not worry about the reputational cost. This is wrong in both directions.

First of all, it’s perfectly possible to have very friendly, anonymous discussion. This is just one example from a thread where people are having a very civil discussion about making tea and coffee. Six thousand comments, and all of them civil, polite and well-mannered.

How did this happen? It it just a nice corner of the Internet that was hidden away, protected from the world, that I’ve now exposed by putting its URL on a big screen? No, it’s because they had a really strong and active set of moderators people who were looking at the content, stamping down on bad behavior, stamping down on people making abusive comments.

So you can do anonymous discussion, it’s just expensive.

For many people, it’s too expensive – but don’t buy into the lie that civilised and anonymous discussion is impossible.

On the other side of this though is the idea that people care about the reputation associated with their real name, and I don’t think that’s true.

I think we can all think of people on a certain website who write all sorts of awful things, some of whom may be presidents of major countries, and somehow do this with impunity. They feel no blowback for the fact that they are utterly awful, reprehensible human beings .

There’s also the problem that defining a real name is actually really hard. Another assumption programmers make about names: some people have multiple names. What your “real” name is can be a really hard thing to define, and it’s probably not a problem you’re actually interested in solving. Whatever platform you’re trying to build, this is probably not it.

The other thing to consider is that connecting wallet names to identities can itself be a source of harassment. We’re all here because we’re in the tech industry. Generally speaking, we associate our wallet names with the name we go by online, in professional circles, at these conferences. That’s because there’s a lot of benefit for us to us doing so – we’re potentially here to get jobs, speaking changes, opportunities – it’s really useful to have our wallet name attached to our online identities.

But we can imagine communities and discussion spaces where that might not be the case. Maybe you’ve got a support group for young trans people who aren’t sure about their identity, and they want to talk to other people and connect with like minds. Maybe you’ve got a group for young LGBT folks or people who are in abusive homes. Maybe you’ve got a community about sex and kink. All perfectly reasonable things to have on the Internet, but if you start connecting those users back to their wallet names – the names they might be known by in the physical world – and in turn allowing people in the physical world to find their online identity, you open the door to other harassment.

The way I prefer is persistent pseudonyms, which are a good middle ground used by a number of services.

So think carefully about your name policies.

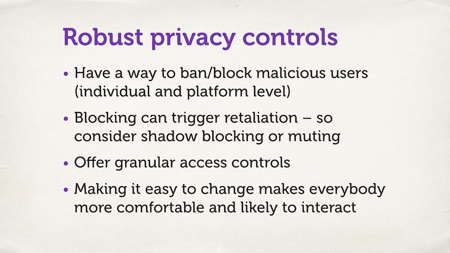

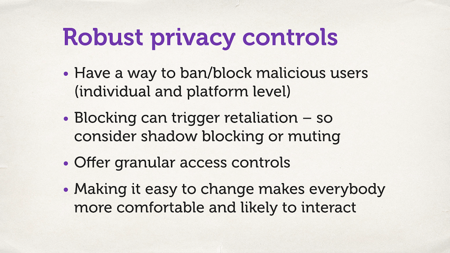

The third thing: robust privacy controls.

At a minimum, you should have a way to ban and block malicious users. Both at a platform and an individual level. I consider this table stakes for most services – but Square cash didn’t do it. I’m still amazed that Slack doesn’t do it. You want a way to kick abusive users off your platform. Even if you really want to be a bastion of free speech (which you probably don’t), there will at some point come somebody writing something you probably don’t want on your platform.

[Ed. I meant to talk more about the value of peer-to-peer blocks, and why they can stop problems at the early stages – but apparently I forgot!]

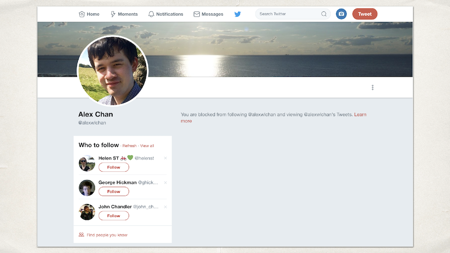

This is one of the things that Twitter actually gets right. They have a blocking feature. This is what it looks like if I’ve blocked you.

What you’ll notice though is that they tell you.

It says “You are blocked from following alexwlchan and viewing alexwlchan’s tweets”. Imagine you went to my Twitter profile after this talk and that’s what you saw. Would that make you feel happy? Respected? Like you were somebody that I liked?

No. You’d probably feel quite annoyed. Quite upset at me. You might decide to take that out on me, right?

Imagine that we were living in the same house, and you discover that I’d blocked you. That might be its own trigger for retaliation – so another thing you can look at things like shadow blocking and muting. Allow people to block somebody without it being visible to the other person that they’re blocked. You can avoid that trigger for retaliation.

Offer granular access controls. The default is public/private, but you can go much more you can go more granular than that. Twitter’s model is to allow posting things only to pre-approved followers, or maybe mutuals only, or down to the level of individual users.

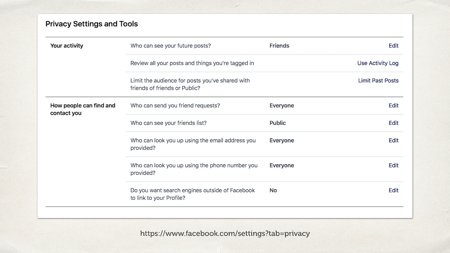

Look at sites like Facebook, LiveJournal, Dreamwidth. They offer really granular permissions for who can see every post. You can decide that on a per-post, per-person basis. This is one of those things people use for really interesting and creative purposes. Aside from just not letting people they don’t like see their content, this is one of those features that people have used in interesting ways.

[Ed. Mutuals only is a feature being offered by Pillowfort. I haven’t tried it yet, but I like the idea.]

An example of Facebook getting it right: they have some pretty granular privacy settings. Not just what I’m writing, I can choose who can see them, who can send me friend requests, who can see my friends lists (I changed that setting after taking this screenshot!). Who can see my future posts.

You can also go back and review your past posts. That’s really important as well – don’t make it immutable. If somebody posts something, and then realises maybe they don’t want that for a wide audience, allow them to go back and change it later.

If you make it easier to change posting visibility, people are more comfortable. They don’t have to publish something to the entire world – and that makes them more comfortable, and more likely to use your service.

Moving along, number 4: don’t rely on technology to solve human problems. If humans are being mean to each other, you need human moderation.

Because you don’t have context – you don’t know everything that happens on (or off) your service.

Here’s an example of a text I got this morning. Someone sent me a picture of a flower – they’re thinking of me.

If it’s a friend from home, and they now I’ve got this big talk today, that’s really nice. If it’s the stalker who rang my hotel room six times last night, and left a bunch of flowers at reception, that’s not so nice. The message has a very different meaning depending on who sent it,

If that’s the only two things your system can see, you don’t have enough information to make a decision. You need the additional context that goes with it; you need to know my relationship with the sender.

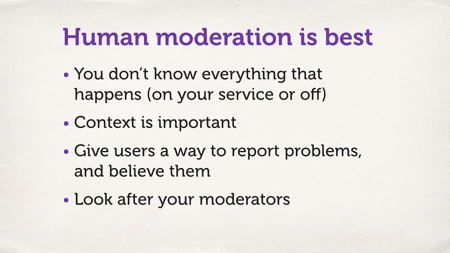

So context is important. Give people a way to report problems, believe them, treat their reports in good faith. Act upon them.

[Ed. I ran out of time to mention this, but I’d point to the Code of Conduct reporting procedure as an example of how to collect reports of harassment.]

Finally, look after your moderators. Today, we’ve only talked about online harassment, personal harassment (it’s only a 25 minute slot!). There are lots of other awful things on the Internet: child pornography, sexual abuse, rape imagery, animal harm, torture imagery.

These are really awful horrific things that your moderators will have to look at and make a judgement on every time somebody reports it. Look after them – make sure they’re supported. Appropriate counselling, enough breaks, and so on, because even just looking at this stuff really hurts people.

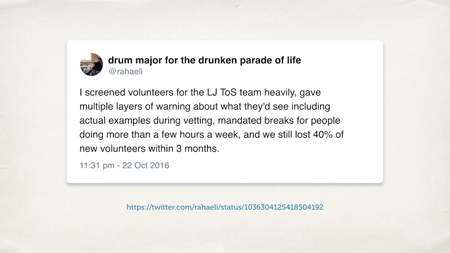

This is a tweet from rahaeli, who did a lot of work on the LiveJournal trust and safety team. It’s part of a larger thread – 40% of people burnt out within three months of having to go through the cesspit of human interaction.

[Ed. I don’t remember rah’s exact role at LiveJournal, but I think they might have been head of the team? If you care about online safety and building good communities, they’re a very good follow on Twitter.]

So human moderation is best, but look after your moderators.

Finally, design with abusive personas in mind.

We’re used to designing with persona where we think about trying to help people. How can we make this flow easier? How can we make our service better? How can we make this process smoother?

Think in the opposite direction: imagine somebody really awful wants to use your service. How are they going to use it to cause harm? How can you make their life as difficult as possible?

Here’s a summary slide: some ways you can protect yours users better:

- Diversify your team

- Think about your name policies

- Robust privacy controls

- Human moderation

- Design with abusive personas in mind

These things won’t catch everything, but they will catch a lot, and they will make your service better.

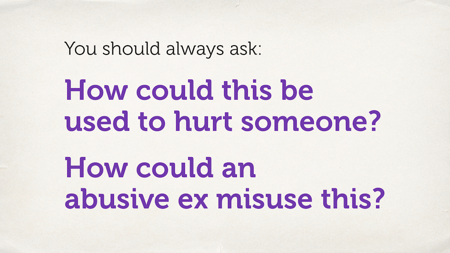

I’ll leave you with this: whenever you’re building something, always ask: How could this be used to hurt someone? How could an abusive ex misuse this?

Because if you don’t answer those questions, somebody else will answer them for you, and your users will get hurt in the process.

Thank you all very much.

Fin.

Whose number is that?

I didn’t take audience Q&A in this session, partly for time and partly because it’s a topic that gets derailed easily. I always prefer having conversations in the hallway track.

Hannah Tucker McLellan asked a very good question about my slides – one you might have wondered if you looked closely. In the slide with a picture of a flower, is that a real person’s phone number? And if so, should I really be sharing it?

Spoiler: I did not accidentally (or deliberately!) leak a real person’s number while talking about other people maliciously leaking personal details online.

Ofcom (the UK telecoms regulator) has reserved blocks of phone numbers for fictional use. I used one of those – from the Cardiff block, because that’s where the conference was being held – not a real person’s number. It’s an Easter egg I put in when I made the slides, and had entirely forgotten about.

Props to Hannah for asking.