How moving to the cloud took Wellcome’s digital collections to new heights

I wrote this article while I was working at Wellcome Collection. It was originally published on their Stacks blog under a CC BY 4.0 license, and is reposted here in accordance with that license.

We want to provide free and unrestricted access to our collections, and we digitise our collections so that we can make them available online. We’ve already digitised hundreds of thousands of items, and put millions of images online — but there’s plenty more to do!

Over the last few years, we’ve moved a lot of our back-end systems into the cloud. This has opened new possibilities for how we manage our digital collections — it’s not just a drop-in replacement, it’s a step change in what we can do.

How we manage our digital collections

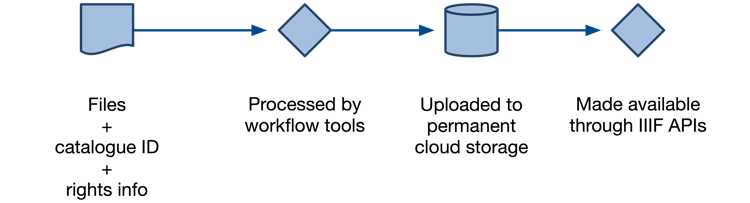

We get some files, either directly from our in-house digitisation team, sent by one of our external digitisation vendors, or born-digital files given to us by a donor.

These go through workflow tools which do certain processing steps, like file format identification and adding fixity checksums. For digitised material we use Goobi; for born-digital material we use Archivematica. This creates additional metadata which is stored with the files.

The processed files are then uploaded to permanent storage, and where possible published online through open, freely-available IIIF APIs. (Not all of our digital collections are available; a subset is restricted or closed in line with our Access Policy, e.g. if the files contain personal information about living people.)

Previously, all of this processing happened on-site, and our files were kept in a mixture of on-premise RAID storage and Amazon S3. We’ve moved this entire process to the cloud, and that gives us a number of very tangible benefits.

What do we get from the cloud?

We can store much bigger files

We replaced our on-premise storage with a new, open-source storage service that’s backed by Amazon S3 and Azure Blob. These cloud services allow you to upload as much data as you like, which is more flexible than our on-prem setup. Previously, new storage had to be ordered weeks or months in advance — but never again will we have to pause our collecting while we wait for new hard drives.

One place where we’ve taken advantage of this flexibility is in our audiovisual collections. When we started processing and ingesting AV material in the cloud, we could move from compressed MPEG2 files to higher quality 2K or 4K files. The higher quality files are much bigger, and obviously more desirable from a preservation point of view, but with our on-premise storage we didn’t have the capacity for that much data. The cloud can not only store these larger files, but it can store them in a cost-effective way.

This is one example of how moving to the cloud has allowed us to make more decisions based on what’s best for the collections, not our technical limitations.

We can go much faster

Our on-premise workflow tools had a fixed capacity, and we’d often hit it! If we got a particularly large batch of new files, those services would get backed up, and sometimes take days or weeks to clear their queues. The queues would clear eventually, but this bottleneck was a limit on our ability to increase our rate of digitisation.

All our cloud services are “elastic” — they can scale up or down based on the work available. At midday on a Tuesday, they’ll be using lots of resources. If you come back at 2am on Sunday, nothing will be running. This means that when a big batch of material arrives, they’ll add more processing capacity to deal with it — and then take it away when it’s done. Now this bottleneck is removed, new material will appear much sooner after it’s digitised.

This also means we don’t need to pass files around the on-site network or download them to our laptops — we can work on them directly in the cloud. This is a big win, especially in the age of hybrid working, when not everybody has a fast Internet connection at home — less time waiting to move files around.

We can reprocess content at scale

Because we have so much capacity, we can do the sort of bulk processing that simply wasn’t feasible in our old system. We have ~100M objects in our permanent storage, but we could reprocess them all in a matter of hours.

One benefit of this is that we don’t need to fixate on picking the one and only “correct” file format for our digital objects. We can convert files into new formats whenever we like, so now we store highest-quality preservation files, and then we create access copies from the preservation copy in different formats. As file format fashion changes, we can create new access copies.

For example, we have a growing pile of Word documents and PowerPoint decks in our born-digital collections. Currently we just store the original file, but at some point we might create PDF derivatives as access copies — and we could do that for all our existing files, not just new ingests. We’re not bound by decisions we’ve already made; we can migrate our digital collections as our needs evolve.

All this means we can handle more files, larger files, and more complex digital objects. We can be more ambitious about the sort of digitisation projects we undertake.

It’s easier to receive files

A few months after I started at Wellcome, we got a new batch of files from a vendor in Cambridge. I drove over to their office, collected a box full of hard drives, wrapped it in towels and bubble wrap, and carried it back to London on the train. Being jostled on the Tube has never been more stressful.

The files arrived safely, but this is obviously sub-optimal.

Vendors can now deliver files directly into our S3 buckets, which is simpler, more secure, and allows us to have lots of small deliveries rather than waiting for one massive batch.

Where next?

It’s important to acknowledge the complexity of moving all our storage and data management to the cloud. It was a multi-year process that required a lot of collaboration between teams, we had to add new skills and people, and it took careful planning and delivery. This wasn’t a quick win.

And it’s not “done” — running this sort of platform is a continuous process. We’ll continue to maintain and extend this infrastructure, and we’ll continue to grow our digital collections — adding 4 to 5 million new images a year. New bottlenecks and bugs will emerge, and we’ll address them as they do.

The cost of this setup is very manageable. Our storage cost scales linearly at a steady ~$25/TB, and that’s for all three copies of our content. Our processing cost is pretty stable, and doesn’t vary much month-to-month.

We’re about to roll our performance improvements to our image servers — as more and more people visit our website, we want to keep it fast and speedy. We’re also looking at presenting born-digital material on our website, so you can browse those files as easily as our digitised collections. And there’s plenty more to come after that.

Looking back, the benefits of building our own platform are clear. It’s more than just numbers on a spreadsheet or abstract technical advances. We’ve removed technical limitations, which means we can make more decisions based on what’s best for the collections, and not be limited by our digital infrastructure.