Adding auto-generated cover images to EPUBs downloaded from AO3

I was chatting with a friend recently, and she mentioned an annoyance when reading fanfiction on her iPad. She downloads fic from AO3 as EPUB files, and reads it in the Kindle app – but the files don’t have a cover image, and so the preview thumbnails aren’t very readable:

She’s downloaded several hundred stories, and these thumbnails make it difficult to find things in the app’s “collections” view.

This felt like a solvable problem. There are tools to add cover images to EPUB files, if you already have the image. The EPUB file embeds some key metadata, like the title and author. What if you had a tool that could extract that metadata, auto-generate an image, and use it as the cover?

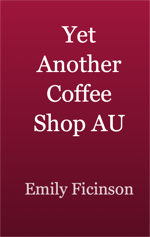

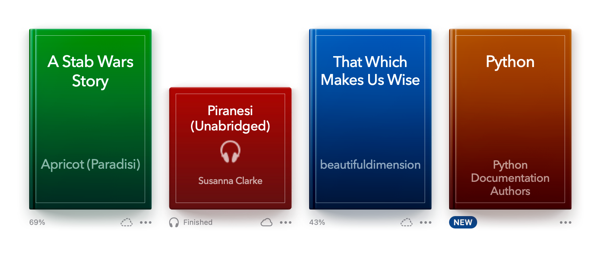

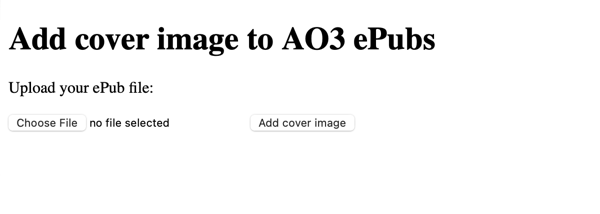

So I built that. It’s a small site where you upload EPUB files you’ve downloaded from AO3, the site generates a cover image based on the metadata, and it gives you an updated EPUB to download. The new covers show the title and author in large text on a coloured background, so they’re much easier to browse in the Kindle app:

If you’d find this helpful, you can use it at alexwlchan.net/my-tools/add-cover-to-ao3-epubs/ Otherwise, I’m going to explain how it works, and what I learnt from building it.

There are three steps to this process:

- Open the existing EPUB to get the title and author

- Generate an image based on that metadata

- Modify the EPUB to insert the new cover image

Let’s go through them in turn.

Open the existing EPUB

I’ve not worked with EPUB before, and I don’t know much about it.

My first instinct was to look for Python EPUB libraries on PyPI, but there was nothing appealing. The results were either very specific tools (convert EPUB to/from format X) or very unmaintained (the top result was last updated in April 2014). I decied to try writing my own code to manipulate EPUBs, rather than using somebody else’s library.

I had a vague memory that EPUB files are zips, so I changed the extension from .epub to .zip and tried unzipping one – and it turns out that yes, it is a zip file, and the internal structure is fairly simple. I found a file called content.opf which contains metadata as XML, including the title and author I’m looking for:

<?xml version='1.0' encoding='utf-8'?>

<package xmlns="http://www.idpf.org/2007/opf" version="2.0" unique-identifier="uuid_id">

<metadata xmlns:opf="http://www.idpf.org/2007/opf" xmlns:dc="http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/" xmlns:dcterms="http://purl.org/dc/terms/" xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance" xmlns:calibre="http://calibre.kovidgoyal.net/2009/metadata">

<dc:title>Operation Cameo</dc:title>

<meta name="calibre:timestamp" content="2025-01-25T18:01:43.253715+00:00"/>

<dc:language>en</dc:language>

<dc:creator opf:file-as="alexwlchan" opf:role="aut">alexwlchan</dc:creator>

<dc:identifier id="uuid_id" opf:scheme="uuid">13385d97-35a1-4e72-830b-9757916d38a7</dc:identifier>

<meta name="calibre:title_sort" content="operation cameo"/>

<dc:description><p>Some unusual orders arrive at Operation Mincemeat HQ.</p></dc:description>

<dc:publisher>Archive of Our Own</dc:publisher>

<dc:subject>Fanworks</dc:subject>

<dc:subject>General Audiences</dc:subject>

<dc:subject>Operation Mincemeat: A New Musical - SpitLip</dc:subject>

<dc:subject>No Archive Warnings Apply</dc:subject>

<dc:date>2023-12-14T00:00:00+00:00</dc:date>

</metadata>

…That dc: prefix was instantly familiar from my time working at Wellcome Collection – this is Dublin Core, a standard set of metadata fields used to describe books and other objects. I’m unsurprised to see it in an EPUB; this is exactly how I’d expect it to be used.

I found an article that explains the structure of an EPUB file, which told me that I can find the content.opf file by looking at the root-path element inside the mandatory META-INF/container.xml file which is every EPUB. I wrote some code to find the content.opf file, then a few XPath expressions to extract the key fields, and I had the metadata I needed.

Generate a cover image

I sketched a simple cover design which shows the title and author.

I wrote the first version of the drawing code in Pillow, because that’s what I’m familiar with. It was fine, but the code was quite flimsy – it didn’t wrap properly for long titles, and I couldn’t get custom fonts to work.

Later I rewrote the app in JavaScript, so I had access to the HTML canvas element. This is another tool that I haven’t worked with before, so a fun chance to learn something new. The API felt fairly familiar, similar to other APIs I’ve used to build HTML elements.

This time I did implement some line wrapping – there’s a measureText() API for canvas, so you can see how much space text will take up before you draw it. I break the text into words, and keeping adding words to a line until measureText tells me the line is going to overflow the page. I have lots of ideas for how I could improve the line wrapping, but it’s good enough for now.

I was also able to get fonts working, so I picked Georgia to match the font used for titles on AO3.

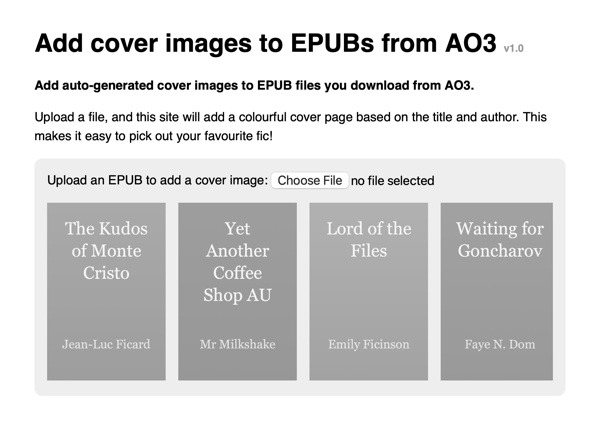

Here are some examples:

I had several ideas for choosing the background colour. I’m trying to help my friend browse her collection of fic, and colour would be a useful way to distinguish things – so how do I use it?

I realised I could get the fandom from the EPUB file, so I decided to use that. I use the fandom name as a seed to a random number generator, then I pick a random colour. This means that all the fics in the same fandom will get the same colour – for example, all the Star Wars stories are a shade of red, while Star Trek are a bluey-green.

This was a bit harder than I expected, because it turns out that JavaScript doesn’t have a built-in seeded random number generator – I ended up using some snippets from a Stack Overflow answer, where bryc has written several pseudorandom number generators in plain JavaScript.

I didn’t realise until later, but I designed something similar to the placeholder book covers in the Apple Books app. I don’t use Apple Books that often so it wasn’t a deliberate choice to mimic this style, but clearly it was somewhere in my subconscious.

One difference is that Apple’s app seems to be picking from a small selection of background colours, whereas my code can pick a much wider variety of colours. Apple’s choices will have been pre-approved by a designer to look good, but I think mine is more fun.

Add the cover image to the EPUB

My first attempt to add a cover image used pandoc:

pandoc input.epub --output output.epub --epub-cover-image cover.jpegThis approach was no good: although it added the cover image, it destroyed the formatting in the rest of the EPUB. This made it easier to find the fic, but harder to read once you’d found it.

So I tried to do it myself, and it turned out to be quite easy! I unzipped another EPUB which already had a cover image. I found the cover image in OPS/images/cover.jpg, and then I looked for references to it in content.opf. I found two elements that referred to cover images:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<package xmlns="http://www.idpf.org/2007/opf" version="3.0" unique-identifier="PrimaryID">

<metadata xmlns:dc="http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/" xmlns:opf="http://www.idpf.org/2007/opf">

<meta name="cover" content="cover-image"/>

…

</metadata>

<manifest>

<item id="cover-image" href="images/cover.jpg" media-type="image/jpeg" properties="cover-image"/>

…

</manifest>

</package>This gave me the steps for adding a cover image to an EPUB file: add the image file to the zipped bundle, then add these two elements to the content.opf.

Where am I going to deploy this?

I wrote the initial prototype of this in Python, because that’s the language I’m most familiar with. Python has all the libraries I need:

- The zipfile module can unpack and modify the EPUB/ZIP

- The xml.etree or lxml modules can manipulate XML

- The Pillow library can generate images

I built a small Flask web app: you upload the EPUB to my server, my server does some processing, and sends the EPUB back to you. But for such a simple app, do I need a server?

I tried rebuilding it as a static web page, doing all the processing in client-side JavaScript. That’s simpler for me to host, and it doesn’t involve a round-trip to my server. That has lots of other benefits – it’s faster, less of a privacy risk, and doesn’t require a persistent connection. I love static websites, so can they do this?

Yes! I just had to find a different set of libraries:

- The JSZip library can unpack and modify the EPUB/ZIP, and is the only third-party code I’m using in the tool

- Browsers include DOMParser for manipulating XML

- I’ve already mentioned the HTML

<canvas>element for rendering the image

This took a bit longer because I’m not as familiar with JavaScript, but I got it working.

As a bonus, this makes the tool very portable. Everything is bundled into a single HTML file, so if you download that file, you have the whole tool. If my friend finds this tool useful, she can save the file and keep a local copy of it – she doesn’t have to rely on my website to keep using it.

What should it look like?

My first design was very “engineer brain” – I just put the basic controls on the page. It was fine, but it wasn’t good. That might be okay, because the only person I need to be able to use this app is my friend – but wouldn’t it be nice if other people were able to use it?

If they’re going to do that, they need to know what it is – most people aren’t going to read a 2,500 word blog post to understand a tool they’ve never heard of. (Although if you have read this far, I appreciate you!) I started designing a proper page, including some explanations and descriptions of what the tool is doing.

I got something that felt pretty good, including FAQs and acknowledgements, and I added a grey area for the part where you actually upload and download your EPUBs, to draw the user’s eye and make it clear this is the important stuff. But even with that design, something was missing.

I realised I was telling you I’d create covers, but not showing you what they’d look like. Aha! I sat down and made up a bunch of amusing titles for fanfic and fanfic authors, so now you see a sample of the covers before you upload your first EPUB:

This makes it clearer what the app will do, and was a fun way to wrap up the project.

What did I learn from this project?

Don’t be scared of new file formats

My first instinct was to look for a third-party library that could handle the “complexity” of EPUB files. In hindsight, I’m glad I didn’t find one – it forced me to learn more about how EPUBs work, and I realised I could write my own code using built-in libraries. EPUB files are essentially ZIP files, and I only had basic needs. I was able to write my own code.

Because I didn’t rely on a library, now I know more about EPUBs, I have code that’s simpler and easier for me to understand, and I don’t have a dependency that may cause problems later.

There are definitely some file formats where I need existing libraries (I’m not going to write my own JPEG parser, for example) – but I should be more open to writing my own code, and not jumping to add a dependency.

Static websites can handle complex file manipulations

I love static websites and I’ve used them for a lot of tasks, but mostly read-only display of information – not anything more complex or interactive. But modern JavaScript is very capable, and you can do a lot of things with it. Static pages aren’t just for static data.

One of the first things I made that got popular was find untagged Tumblr posts, which was built as a static website because that’s all I knew how to build at the time. Somewhere in the intervening years, I forgot just how powerful static sites can be.

I want to build more tools this way.

Async JavaScript calls require careful handling

The JSZip library I’m using has a lot of async functions, and this is my first time using async JavaScript. I got caught out several times, because I forgot to wait for async calls to finish properly.

For example, I’m using canvas.toBlob to render the image, which is an async function. I wasn’t waiting for it to finish, and so the zip would be repackaged before the cover image was ready to add, and I got an EPUB with a missing image. Oops.

I think I’ll always prefer the simplicity of synchronous code, but I’m sure I’ll get better at async JavaScript with practice.

Final thoughts

I know my friend will find this helpful, and that feels great.

Writing software that’s designed for one person is my favourite software to write. It’s not hyper-scale, it won’t launch the next big startup, and it’s usually not breaking new technical ground – but it is useful. I can see how I’m making somebody’s life better, and isn’t that what computers are for? If other people like it, that’s a nice bonus, but I’m really thinking about that one person.

Normally the one person I’m writing software for is me, so it’s extra nice when I can do it for somebody else.

If you want to try this tool yourself, go to alexwlchan.net/my-tools/add-cover-to-ao3-epubs/

If you want to read the code, it’s all on GitHub.