The palm tree that led to Palmyra

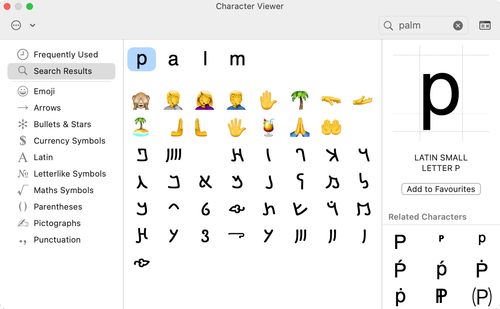

A while ago I was looking for a palm tree emoji, and the macOS Character Viewer suggested a variety of other characters I didn’t recognise:

Some of the curves look a bit like Hebrew, but it’s definitely not that alphabet. I clicked on the first character (𐡱) and learnt that it’s Palmyrene Letter Pe, which is from the Palmyrene alphabet. I’d never heard of Palmyrene, so I knew I was about to learn something.

The Palmyrene Unicode block

These letters are part of the Palmyrene Unicode block, a set of 32 code points for the Palmyrene alphabet and digits. One of the cool things about Unicode is that the proposals for new characters are publicly available on the Unicode Consortium website, and they’re usually pretty readable.

Proposals have to provide some background on the characters they’re proposing. Here’s the introduction from the original proposal in 2010:

The Palmyrene alphabet was used from the first century BCE, in a small independent state established near the Red Sea, north of the Syrian desert between Damascus and the Euphrates. The alphabet was derived as a national script by modification of the customary forms that cursive Aramaic which themselves developed during the first Persian Empire.

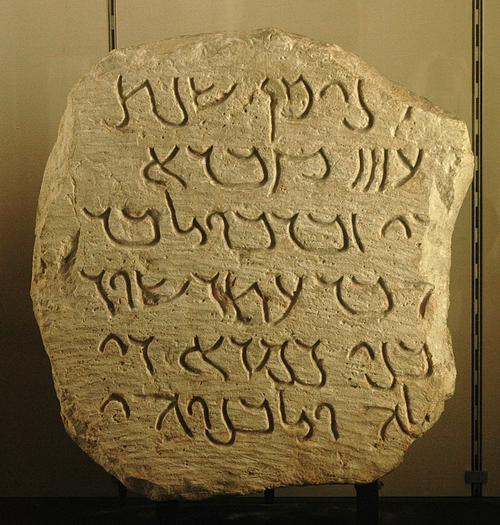

Palmyrene is known from documents distributed over a period from the year 9 BCE until 273 CE, the date of the sack of Palmyra by Aurelian. […] No documents on perishable materials have survived; there are a few painted inscriptions, but many inscriptions on stone.

Here’s an example of a funerary stone inscribed with Palmyrene script, whose shapes match the Unicode characters I didn’t recognise:

The proposal was written by Michael Everson, a prolific contributor who’s submitted hundreds of proposals to add characters to Unicode. His Wikipedia article lists over seventy scripts. He was profiled by the New York Times in 2003 – seven years before proposing Palmyrene – which described his work and his “crucial role in developing Unicode”.

He takes a very long view of his work. Normally I’m sceptical of claims about the longevity of digital work, but Unicode is a rare area where I think it might just last:

“There’s satisfaction in knowing that the work of analyzing and encoding these languages, once done, will never need to be done again,” [Everson] said. “This will be used for the next thousand years.”

And I liked this part at the end:

He likes to tell about how he met the president of the Tibetan Calligraphy Society at a Unicode meeting in Copenhagen. Mr. Everson had helped the organization ensure that Tibetan was included in the standard. The president showed Mr. Everson how to write his name in Tibetan with a highlighter pen.

“He thanked me,” Mr. Everson said with reverence. “I couldn’t believe that, because his organization has been in existence for over a thousand years.”

I spent eight years working in cultural heritage and thinking about the longevity of digital collections, but I never gave much thought to the history or encoding of writing. This is cool and important work, and I should learn more about it.

What are the characters in Palmyrene?

Palmyrene has 22 letters in its alphabet, which expands to 32 Unicode codepoints when you include alternative letters, numbers, and a pair of symbols.

The only letter I recognise is aleph (𐡠), which looks similar to the Hebrew letter aleph ℵ. I know the latter because it’s used by mathematicians to describe the size of infinite sets. It turns out aleph or (alef) is the name of letters in a variety of languages, not all of which look the same – including Phoenician (𐤀), Syriac (ܐ), and Nabatean (𐢁/𐢀).

The other letters have names which are new to me, like heth (𐡧), samekh (𐡯), and gimel (𐡢).

One especially interesting letter is nun, which appears differently depending on whether it’s in the middle of the word (𐡮) or the end (𐡭). This reminds me of the ancient Greek letter sigma, which is either σ or ς. I can’t help but see a passing resemblance between final nun and final sigma, but surely it’s a coincidence – the rest of the alphabets are so different.

The Palmyrene numbers look similar to the Arabic numerals we use today, but not necessarily the same meaning. One, two, three and four are regular tally marks (𐡹, 𐡺, 𐡻, 𐡼). The more unusual characters are five (𐡽), ten (𐡾), and twenty (𐡿) – but again, it’s surely a coincidence that the latter resembles the modern digit 3.

Alongside the letters and numbers, there are two decorative symbols for left/right fleurons (𐡷/𐡸).

Writing about a right-to-left language

Palmyrene is written horizontally from right-to-left, which introduced some new challenges while writing this blog post.

The first issue was in my text editor, which is fairly old and doesn’t have good right-to-left support. I can include Palmyrene characters directly in my text, but it messes up the ordering and text selection. I can navigate the text with the arrow keys, but it behaves in weird ways. To get round this, I used HTML entities in all my source code (for example, 𐡠).

The second issue was in the rendered HTML page, where the Unicode characters affect the ordering on the page. In particular, I wanted to show the characters for 1, 2, 3, 4, in that order, so I wrote the four entities – but the browser uses a bidirectional algorithm and renders the sequence of characters as right-to-left. That’s the opposite of what I wanted:

| HTML: | 𐡹, 𐡺, 𐡻, 𐡼 |

|---|---|

| Output: | 𐡹, 𐡺, 𐡻, 𐡼 |

The fix was to wrap each character in the bidirectional isolate <bdi> element. This tells the browser to isolate the direction of the text within that element, so the direction of each character doesn’t affect the overall sequence. This gave me what I wanted:

| HTML: | <bdi>𐡹</bdi>, <bdi>𐡺</bdi>, <bdi>𐡻</bdi>, <bdi>𐡼</bdi> |

|---|---|

| Output: | 𐡹, 𐡺, 𐡻, 𐡼 |

This is the first time the <bdi> element has appeared on this blog, and I think it’s the first time I’ve used it anywhere.

I took the original screenshot in September. It took me three months to dig into the detail, and I’m glad I did. This is a corner of history and writing that I’d never heard of, and even now I’ve only scratched the surface.

The Palmyrene alphabet is an example of what I call a “fractally interesting” topic. However deep you dig, however much you learn, there’s always more to uncover.