Building a personal archive of the web, the slow way

I manage my bookmarks with a static website. I’ve bookmarked over 2000 pages, and I keep a local snapshot of every page. These snapshots are stored alongside the bookmark data, so I always have access, even if the original website goes offline or changes.

I’ve worked on web archives in a professional setting, but this one is strictly personal. This gives me more freedom to make different decisions and trade-offs. I can focus on the pages I care about, spend more time on quality control, and delete parts of a page I don’t need – without worrying about institutional standards or long-term public access.

In this post, I’ll show you how I built this personal archive of the web: how I save pages, why I chose to do it by hand, and what I do to make sure every page is properly preserved.

This article is the second in a four part bookmarking mini-series:

- Creating a static site for all my bookmarks – why I bookmark, why I use a static site, and how it works.

- Creating a local archive of all my bookmarks (this article)

- What I learnt about making websites by reading two thousand web pages – how to write thoughtful HTML, new-to-me features of CSS, and some quirks and relics I found while building my personal web archive.

- My favourite websites from my bookmark collection – websites that change randomly, that mirror the real world, or even follow the moon and the sun, plus my all-time favourite website design.

What do I want from a web archive?

I’m building a personal web archive – it’s just for me. I can be very picky about what it contains and how it works, because I’m the only person who’ll read it or save pages. It’s not a public resource, and nobody else will ever see it.

This means it’s quite different to what I’d do in a professional or institutional setting. There, the priorities are different: automation over manual effort, immutability over editability, and a strong preference for content that can be shared or made public.

I want a complete copy of every web page

I want my archive to have a copy of every page I’ve bookmarked, and for each copy to be a good substitute for the original. It should include everything I need to render the page – text, images, videos, styles, and so on.

If the original site changes or goes offline, I should still be able to see the page as I saved it.

I want the archive to live on my computer

I don’t want to rely on an online service which could break, change, or be shut down.

I learnt this the hard way with Pinboard. I was paying for an archiving account, which promised to save a copy of all my bookmarks. But in recent years it became unreliable – sometimes it would fail to archive a page, and sometimes I couldn’t retrieve a supposedly saved page.

It should be easy to save new pages

I save a couple of new bookmarks a week. I want to keep this archive up-to-date, and I don’t want adding pages to be a chore.

It should support private or paywalled pages

I read a lot of pages which aren’t on the public web, stuff behind paywalls or login screens. I want to include these in my web archive.

Many web archives only save public content – either because they can’t access private content to save, or they couldn’t share if it they did. This makes it even more important that I keep my own copy of private pages, because I may not find another.

It should be possible to edit snapshots

This is both additive and subtractive.

Web pages can embed external resources, and sometimes I want those resources in my archive. For example, suppose somebody publishes a blog post about a conference talk, and embeds a YouTube video of them giving the talk. I want to download the video, not just the YouTube embed code.

Web pages also contain a lot of junk that I don’t care about saving – ads, tracking, pop-ups, and more. I want to cut all that stuff out, and just keep the useful parts. It’s like taking clippings from a magazine: I want the article, not the ads wrapped around it.

What does my web archive look like?

I treat my archived bookmarks like the bookmarks site itself: as static files, saved in folders on my local filesystem.

A static folder for every page

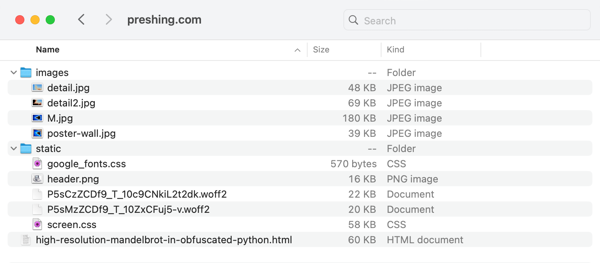

For every page, I have a folder with the HTML, stylesheets, images, and other linked files. Each folder is a self-contained “mini-website”. If I want to look at a saved page, I can just open the HTML file in my web browser.

images and static, which keeps things simple and readable. I don’t care about the exact URL paths from the original site.Any time the HTML refers to an external file, I’ve changed it to fetch the file from the local folder rather than the original website. For example, the original HTML might have an <img> tag that loads an image from https://preshing.com/~img/poster-wall.jpg, but in my local copy I’d change the <img> tag to load from images/poster-wall.jpg.

I like this approach because it’s using open, standards-based web technology, and this structure is simple, durable, and easy to maintain. These folder-based snapshots will likely remain readable for the rest of my life.

Why not WARC or WACZ?

Many institutions store their web archives as WARC or WACZ, which are file formats specifically designed to store preserved web pages.

These files contain the saved page, as well as extra information about how the archive was created – useful context for future researchers. This could include the HTTP headers, the IP address, or the name of the software that created the archive.

You can only open WARC or WACZ files with specialist “playback” software, or by unpacking the files from the archive. Both file formats are open standards, so theoretically you could write your own software to read them – archives saved this way aren’t trapped in a proprietary format – but in practice, you’re picking from a small set of tools.

In my personal archive, I don’t need that extra context, and I don’t want to rely on a limited set of tools. It’s also difficult to edit WARC files, which is one of my requirements. I can’t easily open them up and delete all the ads, or add extra files.

I prefer the flexibility of files and folders – I can open HTML files in any web browser, make changes with ease, and use whatever tools I like.

How do I save a local copy of each web page?

I save every page by hand, then I check it looks good – that I’ve saved all the external resources like images and stylesheets.

This manual inspection gives me the peace of mind to know that I really have saved each web page, and that it’s a high quality copy. I’m not going to open a snapshot in two years time only to discover that I’m missing a key image or illustration.

Let’s go through that process in more detail.

Saving a single web page by hand

I start by saving the HTML file, using the “Save As” button in my web browser.

I open that file in my web browser and my text editor. Using the browser’s developer tools, I look for external files that I need to save locally – stylesheets, fonts, images, and so on. I download the missing files, edit the HTML in my text editor to point at the local copy, then reload the page in the browser to see the result. I keep going until I’ve downloaded everything, and I have a self-contained, offline copy of the page.

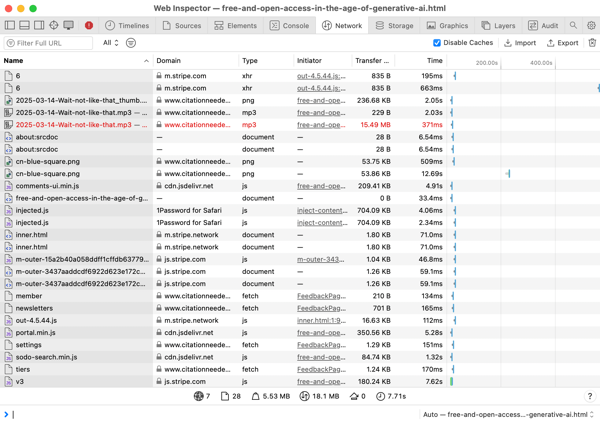

Most of my time in the developer tools is spent in two tabs.

I look at the Network tab to see what files the page is loading. Are they being served from my local disk, or fetched from the Internet? I want everything to come from disk.

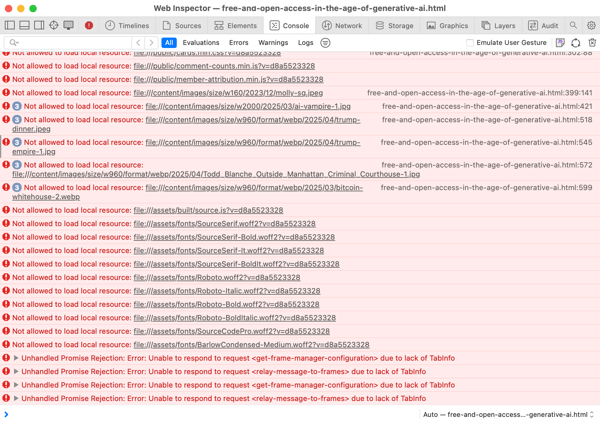

I check the Console tab for any errors loading the page – some image that can’t be found, or a JavaScript file that didn’t load properly. I want to fix all these errors.

I spend a lot of time reading and editing HTML by hand. I’m fairly comfortable working with other people’s code, and it typically takes me a few minutes to save a page. This is fine for the handful of new pages I save every week, but it wouldn’t scale for a larger archive.

Once I’ve downloaded everything the page needs, eliminated external requests, and fixed the errors, I have my snapshot.

Deleting all the junk

As I’m saving a page, I cut away all the stuff I don’t want. This makes my snapshots smaller, and pages often shrank by 10–20×. The junk I deleted includes:

Ads. So many ads. I found one especially aggressive plugin that inserted an advertising

<div>between every single paragraph.Banners for time-sensitive events. News tickers, announcements, limited-time promotions, and in one case, a museum’s bank holiday opening hours.

Inline links to related content. There are many articles where, every few paragraphs, you get a promo for a different article. I find this quite distracting, especially as I’m already reading the site! I deleted all those, so my saved articles are just the text.

Cookie notices, analytics, tracking, and other services for gathering “consent”. I don’t care what tracking tools a web page was using when I saved it, and they’re a complete waste of space in my personal archive.

As I was editing the page in my text editor, I’d look for <script> and <iframe> elements. These are good indicators of the stuff I want to remove – for example, most ads are loaded in iframes. A lot of what I save is static content, where I don’t need the interactivity of JavaScript. I can remove it from the page and still have a useful snapshot.

In my personal archive, I think these deletions are a clear improvement. Snapshots load faster, they’re easier to read, and I’m not preserving megabytes of junk I’ll never use. But I’d be a lot more cautious doing this in a public context.

Institutional web archives try to preserve web pages exactly as they were. They want researchers to trust that they’re seeing an authentic representation of the original page, unchanged in content or meaning. Deleting anything from the page, however well-intentioned, might undermine that trust – who decides what gets deleted? What’s cruft to me might be a crucial clue to someone else.

Using templates for repeatedly-bookmarked sites

For big, complex websites that I bookmark often, I’ve created simple HTML templates.

When I want to save a new page, I discard the original HTML, and I just copy the text and images into the template. It’s a lot faster than unpicking the site’s HTML every time, and I’m saving the content of the article, which is what I really care about.

I was inspired by AO3 (the Archive of Our Own), a popular fanfiction site. You can download copies of every story in multiple formats, and they believe in it so strongly that everything published on their site can be downloaded. Authors don’t get to opt out.

An HTML download from AO3 looks different to the styled version you’d see browsing the web:

But the difference is only cosmetic – both files contain the full text of the story, which is what I really care about. I don’t care about saving a visual snapshot of what AO3 looks like.

Most sites don’t offer a plain HTML download of their content, but I know enough HTML and CSS to create my own templates. I have a dozen or so of these templates, which make it easy to create snapshots of sites I visit often – sites like Medium, Wired, and the New York Times.

Backfilling my existing bookmarks

When I decided to build a new web archive by hand, I already had partial collections from several sources – Pinboard, the Wayback Machine, and some personal scripts.

I gradually consolidated everything into my new archive, tackling a few bookmarks a day: fixing broken pages, downloading missing files, deleting ads and other junk. I had over 2000 bookmarks, and it took about a year to migrate all of them. Now I have a collection where I’ve checked everything by hand, and I know I have a complete set of local copies.

I wrote some Python scripts to automate common cleanup tasks, and I used regular expressions to help me clean up the mass of HTML. This code is too scrappy and specific to be worth sharing, but I wanted to acknowledge my use of automation, albeit at a lower level than most archiving tools. There was a lot of manual effort involved, but it wasn’t entirely by hand.

Now I’m done, there’s only one bookmark that seems conclusively lost – a review of Rogue One on Dreamwidth, where the only capture I can find is a content warning interstitial.

I consider this a big success, but it was also a reminder of how fragmented our internet archives are. Many of my snapshots are “franken-archives” – stitched together from multiple sources, combining files that were saved years apart.

Backing up the backups

Once I have a website saved as a folder, that folder gets backed up like all my other files.

I use Time Machine and Carbon Copy Cloner to back up to a pair of external SSDs, and Backblaze to create a cloud backup that lives outside my house.

Why not use automated tools?

I’m a big fan of automated tools for archiving the web, I think they’re an essential part of web preservation, and I’ve used many of them in the past.

Tools like ArchiveBox, Webrecorder, and the Wayback Machine have preserved enormous chunks of the web – pages that would otherwise be lost. I paid for a Pinboard archiving account for a decade, and I search the Internet Archive at least once a week. I’ve used command-line tools like wget, and last year I wrote my own tool to create Safari webarchives.

The size and scale of today’s web archives are only possible because of automation.

But automation isn’t a panacea, it’s a trade-off. You’re giving up accuracy for speed and volume. If nobody is reviewing pages as they’re archived, it’s more likely that they’ll contain mistakes or be missing essential files.

When I reviewed my old Pinboard archive, I found a lot of pages that weren’t archived properly – they had missing images, or broken styles, or relied on JavaScript from the original site. These were web pages I really care about, and I thought I had them saved, but that was a false sense of security. I’ve found issues like this whenever I’ve used automated tools to archive the web.

That’s why I decided to create my new archive manually – it’s much slower, but it gives me the comfort of knowing that I have a good copy of every page.

What I learnt about archiving the web

Lots of the web is built on now-defunct services

I found many pages that rely on third-party services that no longer exist, like:

- Photo sharing sites – some I’d heard of (Twitpic, Yfrog), others that were new to me (phto.ch)

- Link redirection services – URL shorteners and sponsored redirects

- Social media sharing buttons and embeds

This means that if you load the live site, the main page loads, but key resources like images and scripts are broken or missing.

Just because the site is up, doesn’t mean it’s right

One particularly insidious form of breakage is when the page still exists, but the content has changed. Here’s an example: a screenshot from an iTunes tutorial on LiveJournal that’s been replaced with an “18+ warning”:

This kind of failure is hard to detect automatically – the server is returning a valid response, just not the one you want. That’s why I wanted to look at every web page with my eyes, and not rely on a computer to tell me it was saved correctly.

Many sites do a poor job of redirects

I was surprised by how many web pages still exist, but the original URLs no longer work, especially on large news sites. Many of my old bookmarks now return a 404, but if you search for the headline, you can find the story at a completely different URL.

I find this frustrating and disappointing. Whenever I’ve restructured this site, I always set up redirects because I’m an old-school web nerd and I think URLs are cool – but redirects aren’t just about making me feel good. Keeping links alive makes it easier to find stuff in your back catalogue – without redirects, most people who encounter a broken link will assume the page was deleted, and won’t dig further.

Images are getting easier to serve, harder to preserve

When the web was young, images were simple. You wrote an <img src="…"> tag in your HTML, and that was that.

Today, images are more complicated. You can provide multiple versions of the same image, or control when images are loaded. This can make web pages more efficient and accessible, but harder to preserve.

There are two features that stood out to me:

Lazy loading is a technique where a web page doesn’t load images or resources until they’re needed – for example, not loading an image at the bottom of an article until you scroll down.

Modern lazy loading is easy with

<img loading="lazy">, but there are lots of sites that were built before that attribute was widely-supported. They have their own code for lazy loading, and every site behaves a bit differently. For example, a page might load a low-res image first, then swap it out for a high-res version with JavaScript. But automated tools can’t always run that JavaScript, so they only capture the low-res image.The

<picture>tag allows pages to specify multiple versions of an image. For example:- A page could send a high-res image to laptops, and a low-res images to phones. This is more efficient; you’re not sending an unnecessarily large image to a small screen.

- A page could send different images based on your colour scheme. You could see a graph on a white background if you use light mode, or on black if you use dark mode.

If you preserve a page, which images should you get? All of them? Just one? If so, which one? For my personal archive, I always saved the highest resolution copy of each image, but I’m not sure that’s the best answer in every case.

On the modern web, pages may not look the same for everyone – different people can see different things. When you’re preserving a page, you need to decide which version of it you want to save.

There’s no clearly-defined boundary of what to collect

Once you’ve saved the initial HTML page, what else do you save?

Some automated tools will aggressively follow every link on the page, and every link on those pages, and every link after that, and so on. Others will follow simple heuristics, like “save everything linked from the first page, but no further”, or “save everything up to a fixed size limit”.

I struggled to come up with a good set of heuristics for my own approach, and I was often making decisions on a case-by-case basis. Here are two examples:

I’ve bookmarked blog posts about conferences talks, where authors embed a YouTube video of them giving the talk. I think the video is a key part of the page, so I want to download it – but “download all embeds and links” would be a very expensive rule.

I’ve bookmarked blog posts that comment on scientific papers. Usually the link to the original paper doesn’t go directly to the PDF, but to a landing page on a site like arXiv.

I want to save the PDF because it’s important context for the blog post, but now I’m saving something two clicks away from the original post – which would be even more expensive if applied as a universal rule.

This is another reason why I’m really glad I build my archive by hand – I could make different decisions based on the content and context.

Should you do this?

I can recommend having a personal web archive. Just like I keep paper copies of my favourite books, I now keep local copies of my favourite web pages. I know that I’ll always be able to read them, even if the original website goes away.

It’s harder to recommend following my exact approach. Building my archive by hand took nearly a year, probably hundreds of hours of my free time. I’m very glad I did it, I enjoyed doing it, and I like the result – but it’s a big time commitment, and it was only possible because I have a lot of experience building websites.

Don’t let that discourage you – a web archive doesn’t have to be fancy or extreme.

If you take a few screenshots, save some PDFs, or download HTML copies of your favourite fic, that’s a useful backup. You’ll have something to look at if the original web page goes away.

If you want to scale up your archive, look at automated tools. For most people, they’re a better balance of cost and reward than saving and editing HTML by hand. But you don’t need to, and even a folder with just a few files is better than nothing.

When I was building my archive – and reading all those web pages – I learnt a lot about how the web is built. In part 3 of this series, I’ll share what that process taught me about making websites.

If you’d like to know when that article goes live, subscribe to my RSS feed or newsletter!