The Internet forgets, but I don’t want to

I grew up alongside social media, as it was changing from nerd curiosity to mainstream culture. I joined Twitter and Tumblr in the early 2010s, and I stayed there for over a decade. Those spaces shaped my adult life: I met friends and partners, found a career in cultural heritage, and discovered my queer identity.

That impact will last a long time. The posts themselves? Not so much.

Social media is fragile, and it can disappear quickly. Sites get sold, shut down or blocked. People close their accounts or flee the Internet. Posts get deleted, censored or lost by platforms that don’t care about permanence. We live in an era of abundant technology and storage, but the everyday record of our lives is disappearing before our eyes.

I want to remember social media, and not just as a vague memory. I want to remember exactly what I read, what I saw, what I wrote. If I was born 50 years ago, I’m the sort of person who’d keep a scrapbook full of letters and postcards – physical traces of the people who mattered to me. Today, those traces are digital.

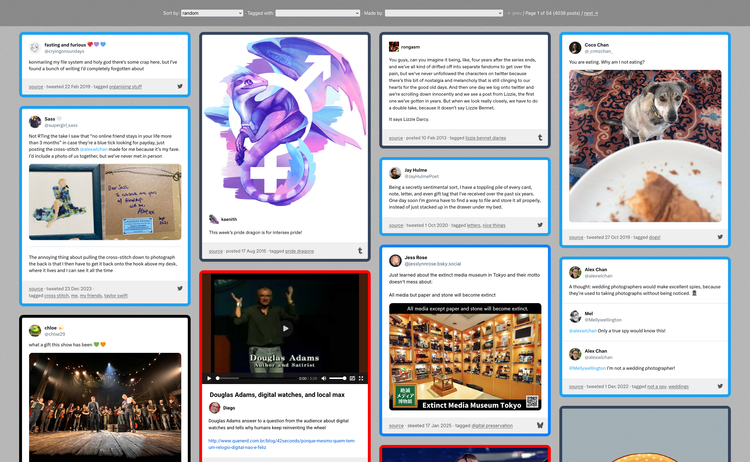

I don’t trust the Internet to remember for me, so I’ve built my own scrapbook of social media. It’s a place where I can save the posts that shaped me, delighted me, or just stuck in my mind.

It’s a static site where I can save conversations from different services, enjoy them in my web browser, and search them using my own tags. It’s less than two years old, but it already feels more permanent than many social media sites. This post is the first in a three-part series about preserving social media, based on both my professional and personal experience.

The long road to a lasting archive

Before I ever heard the phrase “digital preservation”, I knew I wanted to keep my social media. I wrote scripts to capture my conversations and stash them away on storage I controlled.

Those scripts worked, technically, but the end result was a mess. I focusing on saving data, and organisation and presentation were an afterthought. I was left with disordered folders full of JSON and XML files – archives I couldn’t actually use, let along search or revisit with any joy.

I’ve tried to solve this problem more times than I can count. I have screenshots of at least a dozen different attempts, and there are probably just as many I’ve forgotten.

For the first time, though, I think I have a sustainable solution. I can store conversations, find them later, and the tech stack is simple enough to keep going for a long time. Saying something will last always has a whiff of hubris, especially if software is involved, but I have a good feeling.

Looking back, I realise my previous attempts failed because I focused too much on my tools. I kept thinking that if I just picked the right language, or found a better framework, or wrote cleaner code, I’d finally land on a permanent solution. The tools do matter – and a static site will easily outlive my hacky Python web apps – but other things are more important.

What I really needed was a good data model. Every earlier version started with a small schema that could hold simple conversations, which worked until I tried to save something more complex. Whenever that happened, I’d make a quick fix, thinking about the specific issue rather than the data model as a whole. Too many one-off changes and everything would become a tangled mess, which is usually when I’d start the next rewrite.

This time, I thought carefully about the shape of the data. What’s worth storing, and what’s the best way to store it? How do I clean, validate, and refine my data? How do I design a data schema that can evolve in a more coherent way? More than any language or framework choice, I think this is what will finally give this project some sticking power.

How it works

A static site, viewed in the browser

I store metadata in a machine-readable JSON/JavaScript file, and present it as a website that I can open in my browser. Static sites give me a lightweight, flexible way to save and view my data, in a format that’s widely supported and likely to remain usable for a long time.

This is a topic I’ve written about at length, including a detailed explanation of my code.

Conversations as the unit of storage

Within my scrapbook, the unit of storage is a conversation – a set of one or more posts that form a single thread. If I save one post in a conversation, I save them all. This is different to many other social media archives, which only save one post at a time.

The surrounding conversation is often essential to understanding a post. Without it, posts can be difficult to understand and interpret later. For example, a tweet where I said “that’s a great idea!” doesn’t make sense unless you know what I was replying to. Storing all the posts in a conversation together means I always have that context.

A different data model and renderer for each site

A big mistake I made in the past was trying to shoehorn every site into the same data model.

The consistency sounds appealing, but different sites are different. A tweet is a short fragment of plain text, sometimes with attached media. Tumblr posts are longer, with HTML and inline styles. On Flickr the photo is the star, with text-based metadata as a secondary concern.

It’s hard to create a single data model that can store a tweet and a Tumblr post and a Flickr picture and the dozen other sites I want to support. Trying to do so always led me to a reductive model that over-simplified the data.

For my scrapbook, I’m avoiding this problem by creating a different data model for each site I want to save. I can define the exact set of fields used by that site, and I can match the site’s terminology.

Here’s one example: a thread from Twitter, where I saved a tweet and one of the replies. The site, id, and meta are common to the data model across all sites, then there are site-specific fields in the body – in this example, the body is an array of tweets.

{

"site": "twitter",

"id": "1574527222374977559",

"meta": {

"tags": ["trans joy", "gender euphoria"],

"date_saved": "2025-10-31T07:31:01Z",

"url": "https://www.twitter.com/alexwlchan/status/1574527222374977559"

},

"body": [

{

"id": "1574527222374977559",

"author": "alexwlchan",

"text": "prepping for bed, I glanced in a mirror\n\nand i was struck by an overwhelming sense of feeling beautiful\n\njust from the angle of my face and the way my hair fell around over it\n\ni hope i never stop appreciating the sense of body confidence and comfort i got from Transition 🥰",

"date_posted": "2022-09-26T22:31:57Z"

},

{

"id": "1574527342470483970",

"author": "oldenoughtosay",

"text": "@alexwlchan you ARE beautiful!!",

"date_posted": "2022-09-26T22:32:26Z",

"entities": {

"hashtags": [],

"media": [],

"urls": [],

"user_mentions": ["alexwlchan"]

},

"in_reply_to": {

"id": "1574527222374977559",

"user": "alexwlchan"

}

}

}

]

}If this was a conversation from a different site, say Tumblr or Instagram, you’d see something different in the body.

I store all the data as JSON, and I keep the data model small enough that I can fill it in by hand.

I’ve been trying to preserve my social media for over a decade, so I have a good idea of what fields I look back on and what I don’t. For example, many social media websites have metrics – how many times a post was viewed, starred, or retweeted – but I don’t keep them. I remember posts because they were fun, thoughtful, or interesting, not because they hit a big number.

Writing my own data model means I know exactly when it changes. In previous tools, I only stored the raw API response I received from each site. That sounds nice – I’m saving as much information as I possibly can! – but APIs change and the model would subtly shift over time. The variation made searching tricky, and in practice I only looked at a small fraction of the saved data.

I try to reuse data structures where appropriate. Conversations from every site have the same meta scheme; conversations from microblogging services are all the same (Twitter, Mastodon, Bluesky, Threads); I have a common data structure for images and videos.

Each data model is accompanied by a rendering function, which reads the data and returns a snippet of HTML that appears in one of the “cards” in my web browser. I have a long switch statement that just picks the right rendering function, something like:

function renderConversation(props) {

switch(props.site) {

case 'flickr':

return renderFlickrPicture(props);

case 'twitter':

return renderTwitterThread(props);

case 'youtube':

return renderYouTubeVideo(props);

…

}

}This approach makes it easy for me to add support for new sites, without breaking anything I’ve already saved. It’s already scaled to twelve different sites (Twitter, Tumblr, Bluesky, Mastodon, Threads, Instagram, YouTube, Vimeo, TikTok, Flickr, Deviantart, Dribbble), and I’m going to add WhatsApp and email in future – which look and feel very different to public social media.

I also have a “generic media” data model, which is a catch-all for images and videos I’ve saved from elsewhere on the web. This lets me save something as a one-off from a blog or a forum without writing a whole new data model or rendering function.

Keyword tagging on every conversation

I tag everything with keywords as I save it. If I’m looking for a conversation later, I think of what tags I would have used, and I can filter for them in the web app. These tags mean I can find old conversations, and allows me to add my own interpretation to the posts I’m saving.

This is more reliable than full text search, because I can search a consistent set of terms. Social media posts don’t always mention their topic in a consistent, easy-to-find phrase – either because it just didn’t fit into the wording, or because they’re deliberately keeping it as subtext. For example, not all cat pictures include the word “cat”, but I tag them all with “cats” so I can find them later.

I use fuzzy string matching to find and fix mistyped tags.

Metadata in JSON/JavaScript, interpreted as a graph

Here’s a quick sketch of how my data and files are laid out on disk:

scrapbook/

├─ avatars/

├─ media/

│ ├─ a/

│ └─ b/

│ └─ bananas.jpg

├─ posts.js

└─ users.jsThis metadata forms a little graph:

All of my post data is in posts.js, which contains objects like the Twitter example above.

Posts can refer to media files, which I store in the media/ directory and group by the first letter of their filename – this keeps the number of files in each subdirectory manageable.

Posts point to their author in users.js. My user model is small – the path of an avatar image in avatars/, and maybe a display name if the site supports it.

Currently, users are split by site, and I can’t correlate users across sites. For example, I have no way to record that @alexwlchan on Twitter and @alex@alexwlchan.net on Mastodon are the same person. That’s something I’d like to do in future.

A large suite of tests

I have a test suite written in Python and pytest that checks the consistency and correctness of my metadata. This includes things like:

- My metadata files match my data model

- Every media file described in the metadata is saved on disk, and every media file saved on disk is described in the metadata

- I have a profile image for the author of every post that I’ve saved

- Every timestamp uses a consistent format

- None of my videos are encoded in AV1 (which can’t play on my iPhone)

I’m doing a lot of manual editing of metadata, and these tests give me a safety net against mistakes. They’re pretty fast, so I run them every time I make a change.

Inspirations and influences

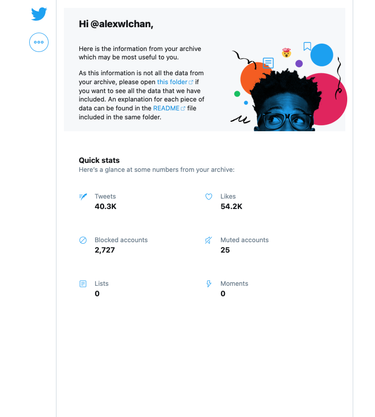

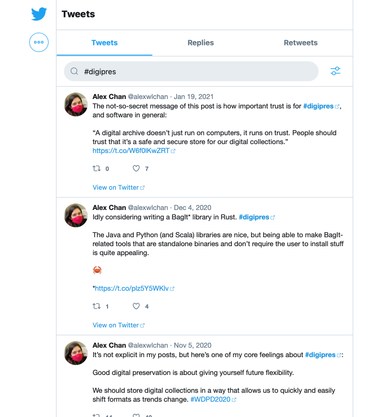

The static website in Twitter’s first-party archives

Pretty much every social media website has a way to export your data, but some exports are better than others. Some sites clearly offer it reluctantly – a zip archive full of JSON files, with minimal documentation or explanation. Enough to comply with data export laws, but nothing more.

Twitter’s archive was much better. When you downloaded your archive, the first thing you’d see was an HTML file called Your archive.html. Opening this would launch a static website where you could browse your data, including full-text search for your tweets:

This approach was a big inspiration for me, and put me on the path of using static websites for tiny archives. It’s a remarkably robust piece of engineering, and these archives will last long after Twitter or X have disappeared from the web.

The Twitter archive isn’t exactly what I want, because it only has my tweets. My favourite moments on Twitter were back-and-forth conversations, and my personal archive only contains my side of the conversation. In my custom scrapbook, I can capture both people’s contributions.

Data Lifeboat at the Flickr Foundation

Data Lifeboat is a project by the Flickr Foundation to create archival slivers of Flickr. I worked at the Foundation for nearly two years, and I built the first prototypes of Data Lifeboat. I joined because of my interest in archiving social media, and the ideas flowed in both directions: personal experiments informed my work, and vice versa.

Data Lifeboat and my scrapbook differ in some details, but the underlying principles are the same.

One of my favourite parts of that work was pushing static websites for tiny archives further than I ever have before. Each Data Lifeboat package includes a viewer app for browsing the contents, which is a static website built in vanilla JavaScript – very similar to the Twitter archive. It’s the most complex static site I’ve ever built, so much so that I had to write a test suite using Playwright.

That experience made me more ambitious about what I can do with static, self-contained sites.

My web bookmarks

Earlier this year I wrote about my bookmarks collection, which I also store in a static site. My bookmarks are mostly long-form prose and video – reference material with private notes. The scrapbook is typically short-form content, often with visual media, often with conversations I was a part of. Both give me searchable, durable copies of things I don’t want to lose.

I built my own bookmarks site because I didn’t trust a bookmarking service to last; I built my social media scrapbook because I don’t trust social media platforms to stick around. They’re two different manifestations of the same idea.

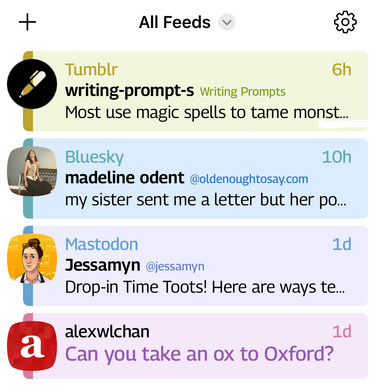

Tapestry, by the Iconfactory

Tapestry is an iPhone app that combines posts from multiple platforms into a single unified timeline – social media, RSS feeds, blogs. The app pulls in content using site-specific “connectors”, written with basic web technologies like JavaScript and JSON.

Although I don’t use Tapestry myself, I was struck by the design, especially the connectors. The idea that each site gets its own bit of logic is what inspired me to consider different data models for each site – and of course, I love the use of vanilla web tech.

Social media embeds on this site

When I embed social media posts on this site, I don’t use the native embeds offered by platforms, which pull in megabytes of of JavaScript and tracking. Instead, I use lightweight HTML snippets styled with my own CSS, an idea I first saw on Dr Drang’s site over thirteen years ago.

The visual appearance of these snippets isn’t a perfect match for the original site, but they’re close enough to be usable. The CSS and HTML templates were a good starting point for my scrapbook.

You can make your own scrapbook, too

I’ve spent a lot of time and effort on this project, and I had fun doing it, but you can build something similar with a fraction of the effort. There are lots of simpler ways to save an offline backup of an online page – a screenshot, a text file, a printout.

If there’s something online you care about and wouldn’t want to lose, save your own copy. The history of the Internet tells us that it will almost certainly disappear at some point.

The Internet forgets, but it doesn’t have to take your memories with it.