Reading a Chinese dictionary / 读一本中文字典

As you might have guessed from my surname (我的姓是陳), I’m half-Chinese. I also speak a smattering of Chinese – I learnt bits of Mandarin and Cantonese as a child, and I’m relearning it as an adult.

In this post, I’m going to explain an aspect of Chinese writing that’s stuck with me since I first learned it – how to use a dictionary.

If I gave you a Chinese–English dictionary, and I asked you to look up the Chinese translation for an English word, you’d probably be okay. The English words are sorted alphabetically, so you know how to find a given word.

But what about the other direction? If I gave you a Chinese word and asked for the English, what would you do?

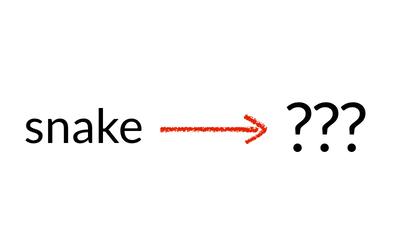

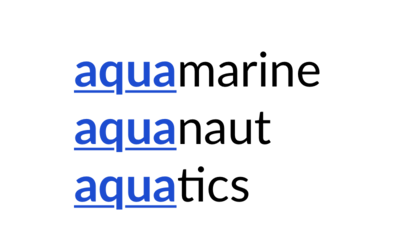

To understand how to use a Chinese dictionary, we need to understand radicals. A radical is a component of a written Chinese character that often gives you a hint as to its subject or meaning. Sort of like in English, when you can sometimes see common roots that hint at a common concept. For example, if you see an unfamiliar word that starts with “aqua”, you might deduce that it’s something to do with water.

Chinese has much the same – but instead of a sequence of common letters, a radical is a sequence of common strokes.

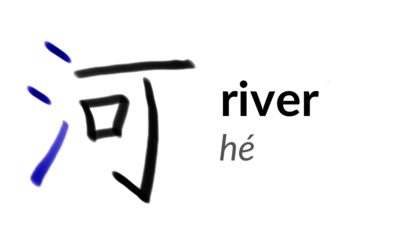

For example, the character for water is 水. This becomes the water radical 氵. If you see it on the left-hand side of a character, you know the character is something to do with water or liquid. These are a few characters that use the water radical:

Here’s another example: the character for fire is 火. This becomes the fire radical, which usually signifies characters related to heat or burning.

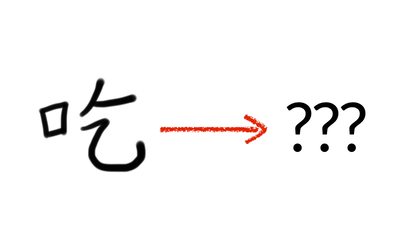

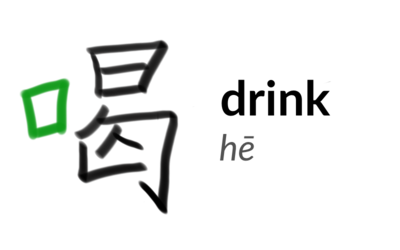

Here’s one more radical that usually appears on the left, the mouth radical:

Notice as well how the right-hand side of 渴 (thirsty) and 喝 (drink) are the same, even though they have different radicals. If you didn’t know what they meant, you could still spot they were related. Chinese characters aren’t drawn arbitrarily – there is a pattern to their strokes and lines.

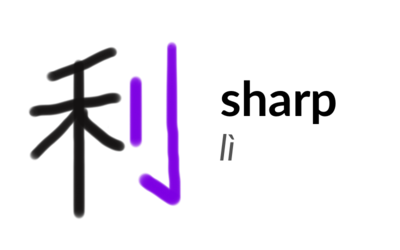

Unfortunately spotting a radical isn’t as simple as just “look at the strokes on the left”. A radical doesn’t always have to appear on the left; it can appear anywhere in the character. Here are two more examples - the grass radical on top of the character, and the knife radical on the right.

Hopefully now you’ve got the idea of radicals – subcomponents of a character that often give a hint about the concept or theme. Chinese has just over 200 radicals, and if you learn Chinese you’ll quickly encounter all the common ones. After a while, you can identify the radicals in a given character. So how do you use that to navigate a dictionary?

Chinese dictionaries are organised by radical –- all the characters with the water radical in one section, the fire radical another, the mouth radical another, and so on. Once you’ve identified the radical, you find the corresponding section of the dictionary, and look up the character there. Within a section, characters are ordered by stroke count – characters with more strokes appear later in the list. (The radical sections are usually ordered by stroke count in the radical, too.)

So to look up a character in a dictionary, you:

- Guess the radical

- Count the strokes in the remaining character

- Look up the characters with that radical and stroke count

For example, let’s take another look at 花. To find it in the dictionary:

- We see the grass radical (艹).

- The remaining strokes are 化, which takes 4 strokes to draw

- We look in the dictionary at the 艹 section, in the list of characters with 4 strokes

Sometimes the radical isn’t obvious, and you need to make a few guesses to get it right – but it usually resolves pretty quickly. (You also need to know how to count strokes; sometimes Chinese elides what look like two strokes into one. For example, 口 is three strokes, not four, because the top and right lines are drawn as a single stroke. Again, this comes with practice.)

So that’s how you look up an unknown character in a Chinese dictionary. Handy, right?

Except… I don’t think I’ve ever actually used that method. By the time I was learning Chinese, I had other, easier ways to find out what an unknown character meant:

- Ask a family member

- Ask my Chinese teacher

- Use Google Translate with handwriting input

But I’m still glad I learnt this approach, because being able to spot radicals is something that stuck. When I started relearning Chinese, spotting radicals came back almost immediately. When I see new characters, I can get a sense of their theme before I know their translation, and it helps me remember all the characters I’ve seen before. Although paper dictionaries are mostly a thing of the past, I hope people are still learning this approach, because knowing about radicals can make Chinese much easier to learn.

谢谢阅读!