Large things living in cold places

I wrote this article while I was working at Wellcome Collection. It was originally published on their Stacks blog under a CC BY 4.0 license, and is reposted here in accordance with that license.

In our digital archive, we store everything in cloud storage. One advantage of cloud storage is that capacity becomes a non-issue — our cloud provider has to worry about buying disks or installing hardware, not us. We upload new files and our bill goes up, but we’ll never run out of disk space.

This is especially useful for one of our current projects, which is the digitisation of our A/V material. We’re trying to digitise all our magnetic media before it becomes unplayable — either because the media itself degrades, or because there are no more working players.

We make two copies of every piece of A/V:

- An access copy: a file that we use to create derivatives suitable for viewing on our website.

- A preservation copy: a file for long-term storage. This is a lossless format with a higher bitrate and resolution than the access copy. We can use it to create new copies if our preferred video formats change, or in cases where we need the highest quality possible.

The preservation copies are big — the biggest so far is 166GB from a single video, and there may be bigger ones to come. We estimate the project is going to triple the amount of data we have in the archive.

Because cloud storage is effectively unlimited, that rough estimate is fine — we don’t need to pre-buy the exact amount of storage we need. But tripling the amount of data means tripling our monthly storage bill. Oof. Can we do something about that?

How much you pay for cloud storage depends on three things:

- How much stuff do you have? Storing more stuff costs more money.

- How much redundancy do you want? It’s cheap to keep one copy of your files, but you’re a single failure away from data loss. If you want better protection, you can store additional copies in different locations, but those extra copies cost more money.

- How quickly do you need to get stuff out? If you need to be able to retrieve things immediately, it’s quite expensive. If you’re willing to wait, your files can be pushed into cheaper storage that’s slower to access.

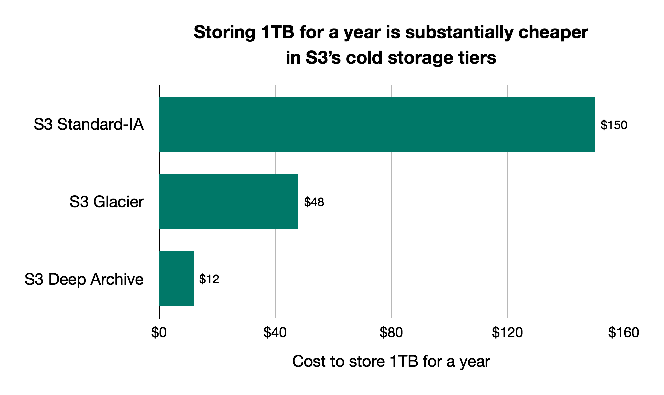

You choose how much redundancy and access you want by selecting a storage class. Each class has a fixed price per GB stored, and that price is smaller for classes with less redundancy or slower access. That gives predictable, linear pricing within a storage class: store twice as much stuff, pay twice as much.

We can’t store less stuff or compromise on redundancy — but we don’t need to get these large preservation copies out very often. They’re not served directly to website users, so we can accept a small delay in retrieving them. We can store our preservation copies in a cold storage class with slower access, and save some money.

This isn’t a new idea — we do the same thing for physical material. Some of our books and archives are kept on-site in London, and the rest are kept in an underground salt mine. There’s a delay to retrieve something from the mine — among other things, it’s a nearly 200 mile drive — but space in Cheshire is cheaper than central London. Different material is stored in different ways.

The primary copy of all our data is in Amazon S3. At the time of writing, S3 has seven storage classes, with two of them cold: Glacier and Deep Archive. They’re both significantly cheaper than the standard class, and typically take several hours to retrieve a file. One difference is that Glacier has expedited retrievals — if you need something quickly, you can retrieve it in minutes, not hours.

We will need expedited retrieval on occasion, so we picked Glacier over Deep Archive. We’ve already used Glacier to store high-resolution masters from our photography workflow — and yes, we do restore files sometimes! — so on balance, the extra cost over Deep Archive is worth it.

(We use Deep Archive elsewhere — for a second, backup copy of all our data.)

We store the primary copy of our large preservation files in Glacier to reduce our storage costs.

One of our priorities for our digital archive is human-readability: it should be possible for a person to understand how the files are organised, even if they don’t have any of our software or databases. The preservation and access copies are the same conceptual object, so we want to group them together within the archive — ideally in the same folder/prefix.

Within S3, the storage class is managed at the per-object level — you can have objects with different storage classes within the same bucket or prefix. This means we can keep the preservation and access copies together.

This is what a digitised A/V item looks like in our storage buckets:

b12345678/

├── METS.xml (metadata file)

├── b12345678.mp4 (access copy, warm storage - Standard IA)

└── b12345678.mxf (preservation copy, cold storage – Glacier)

So how do we tell S3 which objects should go in which storage class?

We’ve created an app that watches files being written to the storage service. When it sees a new preservation file, it adds a tag to the corresponding object in S3. (Tags are key-value pairs that you can attach to individual objects.)

Then we have an S3 lifecycle policy that automatically moves objects with certain tags to Glacier. (We don’t write objects straight to Glacier — immediately after we write an object, we read it back out to verify it against an externally-provided checksum. If we wrote straight to Glacier, we’d be unable to perform this verification step.)

All the pieces of this system are now up and running, and it’s going to be a substantial cost saving as we start to bring in our digitised A/V material:

We can do this because we have a clear understanding of how our files are used and retrieved, and a few simple rules give us a noticeable saving. If you have a big storage bill and you want to make it smaller, understanding how your files are used is often a good place to start. Whatever cloud storage provider you’re using, you can often save money by selecting a storage class that’s appropriate to your use case.

Thanks to Harkiran Dhindsa, Jonathan Tweed, Sarah Bird, and Tom Scott for their help writing this article.