What is psephology?

Yesterday there were local elections in the UK, and this morning I’ve been catching up on the news. As I was reading Yohannes Lowe’s live coverage in the Guardian, I spotted a word I didn’t recognise (emphasis mine):

Labour and the Conservatives are each defending about 1,000 seats, and psephologists predict that the Tories may lose about 500.

A quick trip to Google cleared up my initial confusion: psephologists are experts in psephology, which is the scientific study of elections and voting behaviour. They analyse data from past elections, study voting behaviour, and try to forecast the result of future elections. I’ve seen experts do this sort of analysis in news coverage of elections, but I never knew there was a word for it!

I could have guessed the definition of “psephologist” from the context, but not if I saw it in isolation. Although I recognise the -ology suffix as “the study of something”, I didn’t recognise the pseph- prefix at all, and I was curious where it came from.

Voting and counting in ancient Greece

The Wikipedia article for psephology explains that pseph- comes from the Greek word for pebble, because pebbles were used for voting in ancient Greece. It refers to an article by Annelisa Stephan:

Voting with pebbles? Even allowing for artistic license, it seems the Greeks really did it this way. Voters deposited a pebble into one of two urns to mark their choice; after voting, the urns were emptied onto counting boards for tabulation. […] In ancient Greece a pebble was called a psephos, which gives us the dubious term psephology, the scientific study of elections.

I also found a paper by Alan Boegehold Towards a Study of Athenian Voting Procedure, which describes the use of pebbles when counting votes in ancient Greece. It talks about voting using special bronze discs as ballots, and various mechanisms for keeping ballots secret.

This includes an early example of ballot stuffing, when “thirty men somehow dropped a total of more than sixty ballots into [the urn]”.

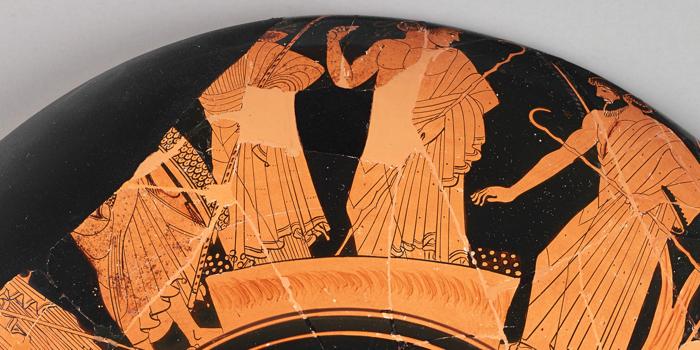

He also describes a scene from Greek vase paintings, in which men cast votes for Ajax and Odysseus using piles of pebbles. One notable aspect is that there doesn’t seem to be any secrecy involved in the voting – we can see who two of the men are voting for.

Athena stands behind a low table (or altar?) which men approach from right and left. They are about to vote; two, in fact, are in the act of voting. That the others have already voted is clear from the two small piles of pebbles on the altar. The pebbles to the left appear to be about double the number of those on the right. They represent votes cast for Odysseus, the victor, while those to the right, fewer, have been cast for Ajax. The two heroes themselves appear at the extreme right and left. Athena, gesturing gracefully with her right hand, certifies Odysseus' victory, although the voting is not yet over.

This feels familiar from modern politics, where the result of an election is often known before the counting is complete. (Sorry Ajax.)

It’s not just for voting

Boegehold also describes the use of pebbles as a way to count things other than votes, when fingers were insufficient. Mostly he’s talking about ancient Greece, but he also mentions pebbles being sealed inside clay tablets as a form of bookkeeping in Mesopotamia. They were placed inside a tablet with an inscription of a sheep (or goat), and the pebbles counted the animals involved.

I came across a similar idea last year while reading It All Adds Up, by Mickaël Launay. I forget the exact time period, but it was early in human civilisation when writing was still uncommon. Somebody owns a flock of sheep, and they send a shepherd out to tend them during the day. They want to know the same number of sheep came back – how do they count them?

They came up with a series of tokens, each with a picture of a sheep. You put them in a jar, and count them to match the sheep who came back. But does the shepherd trust the owner? How do they know the owner won’t add tokens?

So they’d put the tokens in a sealed spherical jar, and both of them would sign it. But how do you know the size of the flock without opening the jar? They’d put marks on the side to count the size – but now why do you need the tokens in the jar at all?

This is an early versions of numbers on “paper”, a more abstract form of counting.

Other uses of the pseph- prefix

I’d never heard of the Greek word psephos; the closest I knew was lithos, for stone. I know lots of English words that use litho- as a root, my favourite being the somewhat whimsical lithobraking. (Stopping your spaceship by ploughing it into a rock.)

By contrast, there only seem to be less English words that use pseph- as a root, and I don’t recognise any of them. Two of the words suggested by Wikipedia are literally about pebbles (psephite/psephitic describes sediment made of pebble-sized fragments), and a third is about their use in counting (isopsephy is adding up the number values of the letters to get a single number).

I was a bit confused by isopsephy initially, but it makes more sense after reading about how pebbles were a tool for counting lots of things, not just votes. That looks like it could be a fun Wikipedia rabbit hole about word counting methods that are a bit like Scrabble, including a similar Hebrew practice called gematria, but I really have to stop now.