Creating a static website for all my bookmarks

I’m storing more and more of my data as static websites, and about a year ago I switched to using a local, static site to manage my bookmarks. It’s replaced Pinboard as the way I track interesting links and cool web pages. I save articles I’ve read, talks I’ve watched, fanfiction I’ve enjoyed.

It’s taken hundreds of hours to get all my bookmarks and saved web pages into this new site, and it’s taught me a lot about archiving and building the web. This post is the first of a four-part series about my bookmarks, and I’ll publish the rest of the series over the next three weeks.

Bookmarking mini-series

- Creating a static site for all my bookmarks (this article)

- Building a personal archive of the web, the slow way – how I built a web archive by hand, the tradeoffs between manual and automated archiving, and what I learnt about preserving the web.

- What I learnt about making websites by reading two thousand web pages – how to write thoughtful HTML, new-to-me features of CSS, and some quirks and relics I found while building my personal web archive.

- My favourite websites from my bookmark collection – websites that change randomly, that mirror the real world, or even follow the moon and the sun, plus my all-time favourite website design.

Why do I bookmark?

I bookmark because I want to find links later

Keeping my own list of bookmarks means that I can always find old links. If I have a vague memory of a web page, I’m more likely to find it in my bookmarks than in the vast ocean of the web. Links rot, websites break, and a lot of what I read isn’t indexed by Google.

This is particularly true for fannish creations. A lot of fan artists deliberately publish in closed communities, so their work is only visible to like-minded fans, and not something that a casual Internet user might stumble upon. If I’m looking for an exact story I read five years ago, I’m far more likely to find it in my bookmarks than by scouring the Internet.

Finding old web pages has always been hard, and the rise of generative AI has made it even harder. Search results are full of AI slop, and people are trying to hide their content from scrapers. Locking the web behind paywalls and registration screens might protect it from scrapers, but it also makes it harder to find.

I bookmark to remember why I liked a link

I write notes on each bookmark I keep, so I remember why a particular link was fun or interesting.

When I save articles, I write a short summary of the key points, information, arguments. I can review a one paragraph summary much faster than I can reread the entire page.

When I save fanfiction, I write notes on the plot or key moments. Is this the story where they live happily ever after? Or does this have a gut wrenching ending that needs a box of tissues?

These summaries could be farmed out to generative AI, but I much prefer writing them myself. I can phrase things in my own words, write down connections to other ideas, and write a more personal summary than I get from a machine. And when I read those summaries back later, I remember writing them, and it revives my memories of the original article or story. It’s slower, but I find it much more useful.

Why use a static website?

I was a happy Pinboard customer for over a decade, but the site feels abandoned. I’ve not had catastrophic errors, but I kept running into broken features or rough edges – search timeouts, unreliable archiving, unexpected outages. There does seem to be some renewed activity in the last few months, but it was too late – I’d already moved away.

I briefly considered Pinboard alternatives like Raindrop, Pocket and Instapaper – but I’d still be trusting an online service. I’ve been burned too many times by services being abandoned, and so I’ve gradually been moving the data I care about to static websites on my local machine. It takes a bit of work to set up, but then I have more control and I’m not worried about it going away.

My needs are pretty simple – I just want a list of links, some basic filtering and search, and a saved copy of all my links. I don’t need social features or integrations, which made it easier to walk away from Pinboard.

I’ve been using static sites for all sorts of data, and I’m enjoying the flexibility and portability of vanilla HTML and JavaScript. They need minimal maintenance and there’s no lock-in, and I’ve made enough of them now that I can create new ones pretty quickly.

What does it look like?

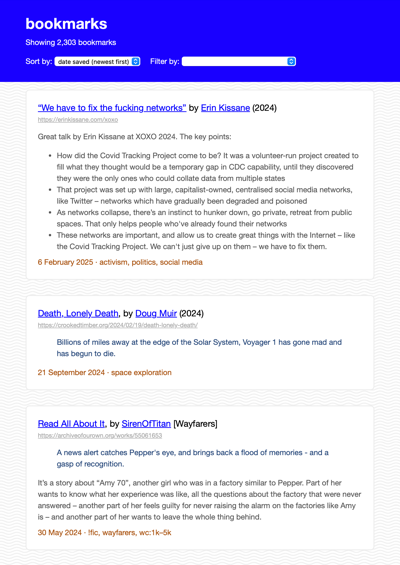

The main page is a scrolling list of all my bookmarks. This is a single page that shows every link, because my collection is small enough that I don’t need pagination.

Each bookmark has a title, a URL, my hand-written summary, and a list of tags.

If I’m looking for a specific bookmark, I can filter by tag or by author, or I can use my browser’s in-page search feature. I can sort by title, date saved, or “random” – this is a fun way to find links I might have forgotten about.

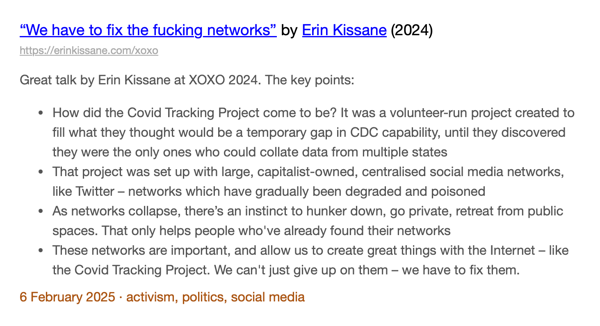

Let’s look at a single bookmark:

The main title is blue and underlined, and the URL of the original page is shown below it. Call me old-fashioned, but I still care about URL design, I think it’s cool to underline links, and I have nostalgia for #0000ff blue. I want to see those URLs.

If I click the URL in grey, I go to the page live on the web. But if I click the title, I go to a local snapshot of the page. Because these are the links I care about most, and links can rot, I’ve saved a local copy of every page as a mini-website – an HTML file and supporting assets. These local snapshots will always be present, and they work offline – that’s why I link to them from the title.

This is something I can only do because this is a personal tool. If a commercial bookmarking website tried to direct users to their self-hosted snapshots rather than the original site, they’d be accused of stealing traffic.

Creating these archival copies took months, and I’ll discuss it more in the rest of this series.

How does it work?

This is a static website built using the pattern I described in How I create static websites for tiny archives. I have my metadata in a JavaScript file, and a small viewer that renders the metadata as an HTML page I can view in my browser.

I’m not sharing the code because it’s deeply personalised and tied to my specific bookmarks, but if you’re interested, that tutorial is a good starting point.

Here’s an example of what a bookmark looks like in the metadata file:

"https://notebook.drmaciver.com/posts/2020-02-22-11:37.html": {

"title": "You should try bad things",

"authors": [

"David R. MacIver"

],

"description": "If you only do things you know are good, eventually some of them will fall out of favour and you'll have an ever-shrinking pool of things.\r\n\r\nSome of the things you think will be bad will end up being good \u2013 trying them helps expand your pool.",

"date_saved": "2024-12-03T07:29:10Z",

"tags": [

"self-improvement"

],

"archive": {

"path": "archive/n/notebook.drmaciver.com/you-should-try-bad-things.html",

"asset_paths": [

"archive/n/notebook.drmaciver.com/static/drmnotes.css",

"archive/n/notebook.drmaciver.com/static/latex.css",

"archive/n/notebook.drmaciver.com/static/pandoc.css",

"archive/n/notebook.drmaciver.com/static/pygments.css",

"archive/n/notebook.drmaciver.com/static/tufte.css"

],

"saved_at": "2024-12-03T07:30:21Z"

},

"publication_year": "2020",

"type": "article"

}I started with the data model from the Pinboard API, which in turn came from an older bookmarking site called Delicious. Over time, I’ve added my own fields. Previously I was putting everything in the title and the tags, but now I can have dedicated fields for things like authors, word count, and fannish tropes.

The archive object is new – that’s my local snapshot of a page. The path points to the main HTML file for the snapshot, and then asset_paths is a list of any other files that get used in the webpage (CSS files, images, fonts and so on). I have a Python script to checks that every archived file has been saved properly.

This is another advantage of writing my own bookmarking tool – I know exactly what data I want to store, and I can design the schema to fit.

When I want to add a bookmark or make changes, I open the JSON in my text editor and make changes by hand. I have a script that checks the file is properly formatted and the archive paths are all correct, and I track changes in Git.

Now you know what my new bookmarking site looks like, and how it works. In part 2, I explain how I created local snapshots of every web page. In part 3, I tell you what that process taught me about building web pages. In the final part, I’ll highlight some fun stuff I found as I went through my bookmarks.